The Hoffnung Concerts

Taken from Gerard Hoffnung: His Biography by Annetta Hoffnung, first published in 1988 by Gordon Frazer Gallery Ltd.

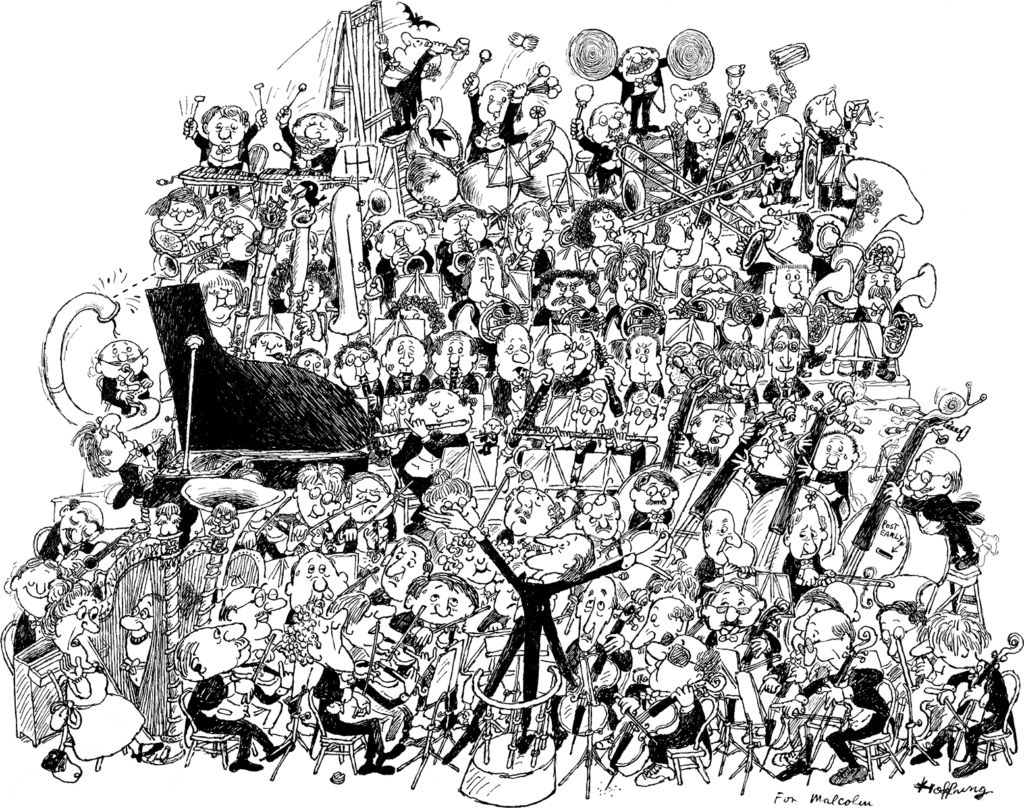

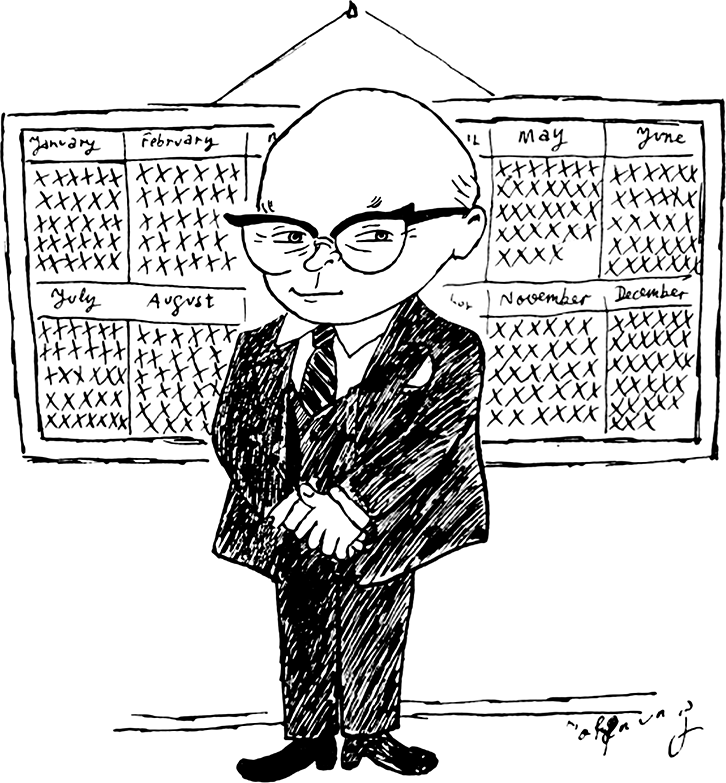

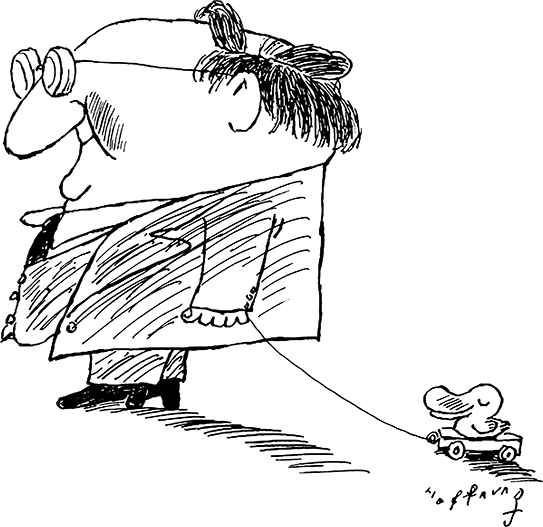

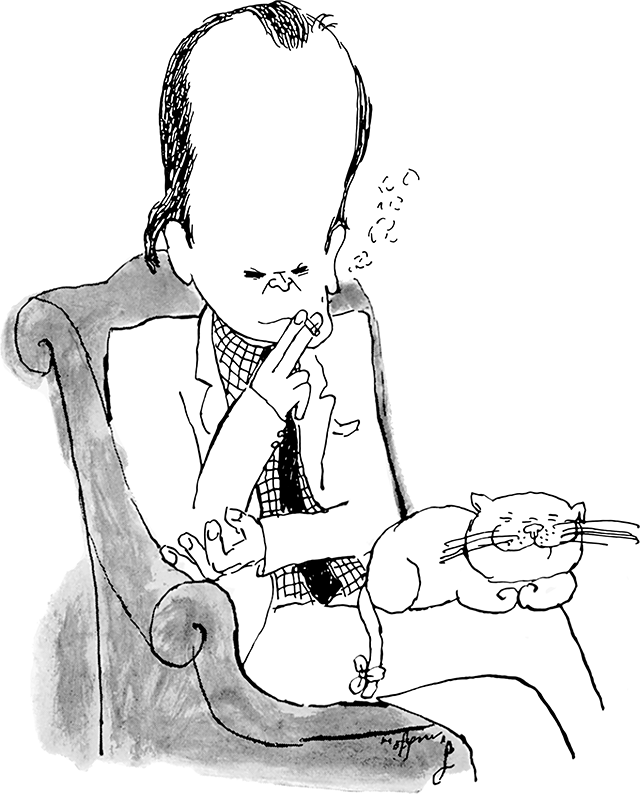

Gerard’s musical drawings and his prowess on the tuba brought many new friends in the world of music. These absorbing and exciting contacts provoked his inventive mind and provided fresh material for caricature. As he was finishing work on the third book of musical cartoons early in 1956, he reflected on why it should be that music was the only art form deprived of comedy. Humour had until then had relatively little outlet in musical performance, although musicians so often display a spontaneous sense of fun. Visually, humour in art had readily been accepted for centuries. Hogarth, Rowlandson, Daumier and, in our day, Steinberg were not merely funny men; their pictures had a place in leading art galleries.

From the early days of orchestral composition, composers had inserted jokes into their works (Mozart best of all practised this habit). Yet there was no great humorous composer. Gerard recalled the intimate evenings of musical humour popular in this country in the past. As long ago as 1946 the BBC’s Third Programme broadcast delightful concerts of musical curiosities and humour devised by Humphrey Searle in collaboration with other composers Alan Rawsthorne, Constant Lambert and E. J Moeran among them. Funny concerts were a more recent phenomenon, and Gerard had taken part in one or two of them. He once played a bicycle pump in an April Fool’s day event devised by Denby Richards in the recital room of the Royal Festival Hall. They were popular entertainments, usually noted for their informality, improvisation and, quite often, lack of organisation. Gerard journeyed once or twice to Liverpool to play his tuba in a similar concert devised by Fritz Spiegl. Pianist and composer Donald Swann, later to team with actor and broadcaster Michael Flanders, recalled, when I spoke to him recently, that he also took part in one of the Liverpool concerts with Gerard – or, at least, very nearly – for the evening stretched to such inordinate lengths that the time limit was reached before he was able to perform his piece. Travelling back on the train to London the next day, he remembers Gerard saying that it seemed to him there was room for something that would really put the comedy of music on the map in a big way. He envisaged a fabulous music festival of symphonic caricature with a vast orchestra and soloists performing works specially commissioned from leading composers. Later, the idea was announced at a press conference and The Times reported on this with dignity:

‘…If we take him aright, he wishes to purge our concert-going of its habitually imperceptive solemnity to indicate the humour in music we forget to notice. A breath of fresh air in the arts is a blessing…’

While The Yorkshire Post had this to say:

‘…By the time Mr Hoffnung came to the end of his announcements, his arms were shooting out in all directions as if he were already conducting from the rostrum. Suddenly he became serious, and his high-pitched voice fell half an octave. It is a serious attempt by my colleagues and myself to bring caricature into symphonic music…’.

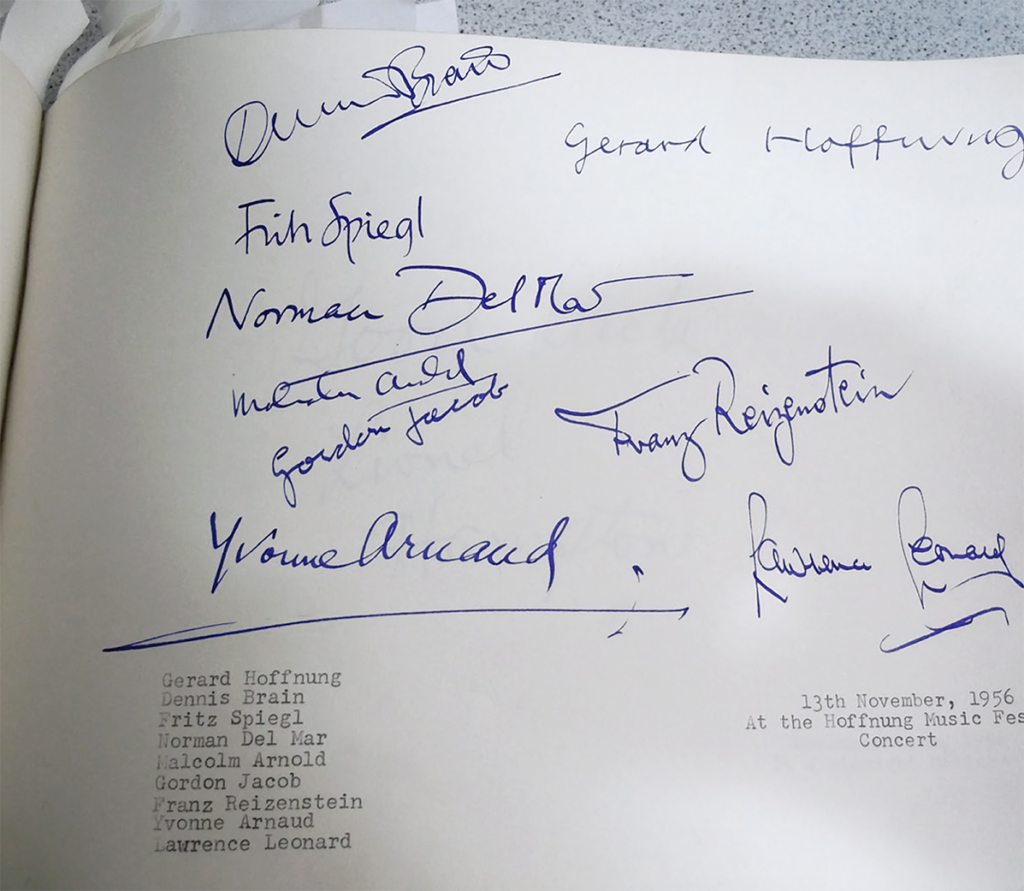

A favourite restaurant of Gerard’s – Wheeler’s in Soho – was the venue chosen for an auspicious occasion to which a number of people were invited to lunch one day. I had my misgivings – the restaurant was expensive and the list of guests long. They included Ernest Bean, the General Manager of the Royal Festival Hall, representatives from EMI and the BBC, Eric Thompson from the Arts Council, Dennis Dobson, Gerard’s publisher, also the broadcaster and classical music critic, John Amis, an old friend who was to organise the first concert and to contribute so excellently to the second one, and the impresario, lan Hunter, all curious as to their host’s intent. It was not until the coffee that Gerard produced his notes and started to explain his plan to the guests.

It was to be a concert to end all concerts. It would consist of entirely new music, not one note of which, at that time had been written. It was to be, explained Gerard, a concert of such artistic merit that it would create a sensation, a combination of superb clowning and good music with the cream of the music profession taking part. And it should take place at the Royal Festival Hall. Possible instrumentation must have been discussed at this meeting because strange rumours soon began to circulate of road-rammers, hot-water bottles and vacuum cleaners filling unlikely roles.

Before the gathering dispersed, Mr Bean had decided that the Royal Festival Hall, then under the auspices of the London County Council, should sponsor the concert and make available a suitable evening later in the year for the occasion. It was April then and the concert was scheduled for November. In the intervening months, ideas sprang up all over the place, works were commissioned, performers participation agreed, posters and programmes designed, and collaborators cajoled in a frenzy of activity I had not experienced before.

Gerard had a knack for triggering off the creative abilities of conductors, composers, artists, soloists and musicians. It was a gift that stood him in good stead, for without the concerted effort of this host of fundamentally serious musicians, his visions could not have materialised. He countered any misgivings, secured their commitment, and enthused and encouraged all involved. They in turn responded with remarkable goodwill and tolerance to the unusual and sometimes outrageous demands made upon them.

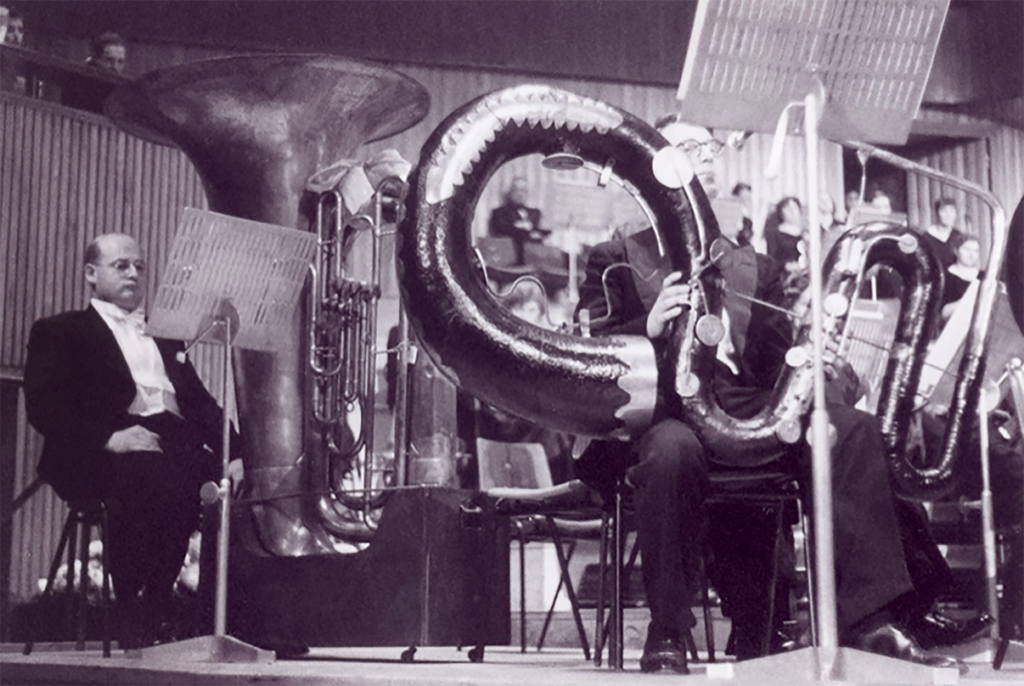

At home we took delivery of an enormous contra-bass serpent, an aged, rare and valuable instrument kindly loaned by the Tolson Memorial Museum in Huddersfield. It arrived earlier than expected and spent the month prior to the concert lying the length of our sitting-room sofa, an interesting if awkward guest. The alphorn stretched down the stairway and across the hall.

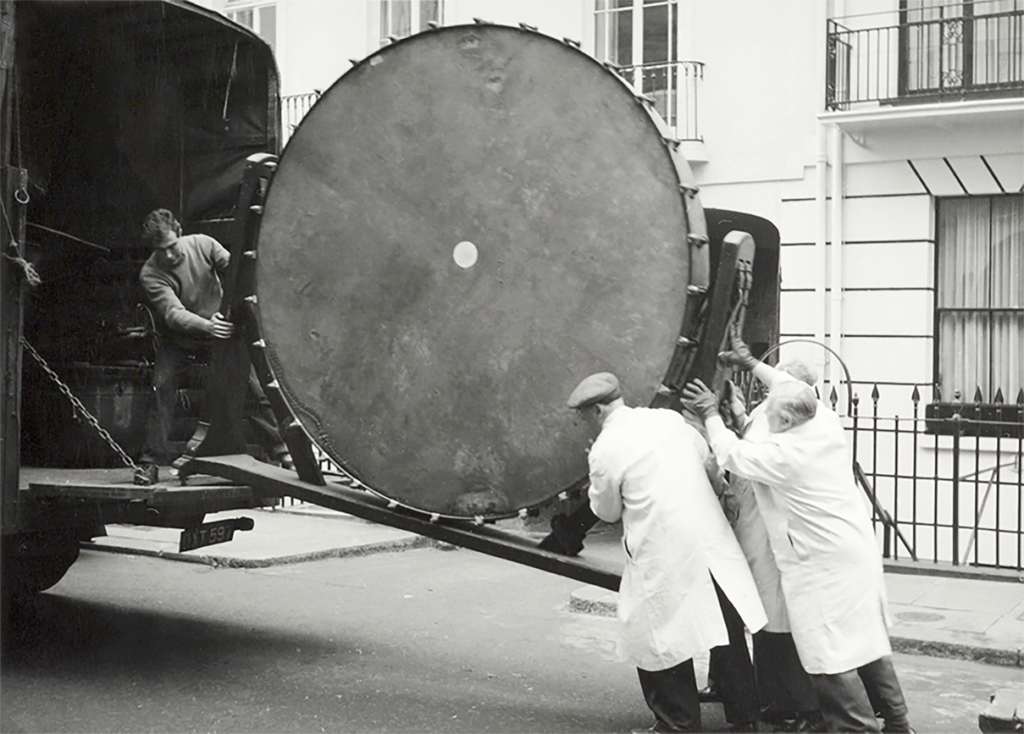

Fortunately for us, the giant bass drum, over eight feet in diameter, was delivered direct to the Royal Festival Hall…

…as was the monster tuba made at the turn of the century for Sousa. It stood over six feet tall and I think I need hardly mention who played this instrument on the night of the concert.

One newspaper remarked afterwards:

‘…Mr Hoffnung played a tuba the size of a blast furnace. Although born in 1925 one cannot suppress the conviction that in fact he sprang fully grown from the bell of this large instrument…’.

Ernest Bean, to whom reference has already been made, wrote about these lively times:

‘…In the course of a year hundreds of famous artists visit the Royal Festival Hall. But there has never been anyone like Gerard Hoffnung. He didn’t visit the Festival Hall; he invaded it. He invaded it with gales of laughter and with the gusto of a great comic personality. I learned to know when Gerard was in the vicinity of the South Bank from the glint of madness and the joyous air of irresponsibility in the eyes of attendants, finance officers, cleaners, electricians and car-park attendants whose paths he had happened to cross. When he was around, the Festival Hall took on the atmosphere of a René Clair (the French writer and film director) film set! I would not say that he was an easy man to work with when he was mounted on one of his wild hobbyhorses! Between the moment that a Hoffnung fantasy was conceived and the night of the concert none of his confederates could call his life his own. They were all liable to be telephoned in the dead of night to be told of the latest outrageous quirk which had alighted athwart the nose of our Mercutio as he lay asleep.

‘I remember one such occasion vividly. One morning there was a knock at my door. After a portentous pause the door opened and inch by inch, foot by foot, there advanced into my room, like the floating objects which enlivened spiritualist seances, a long metal tube with a horn like an elephant’s proboscis. When it had filled the whole length of my office there appeared at the business end, like a conception from one of his own cartoons (I sometimes suspected that Gerard’s cartoons were in actual fact self-portraits seen through a distorted mirror) the round, smiling, cherubic face of Gerard Hoffnung. ‘What do you think of this?’, he asked. ‘Let me play it to you… But it’s no use here… there isn’t room… I’ll tell you what! You go into the street: I’ll put the end through the window: and you can hold an audition from there!’ I endeavoured to point out that the extensive building operations then taking place on the South Bank, with giant electric pile-drivers making the day hideous, would prevent me hearing a note of the music. But he gave me that knowing, conspiratorial smile, the like of which I have never seen on any other human face, and gently urged me to do as I was told. As usual, I did. He put the mouthpiece to his lips. A look of unalloyed bliss suffused his features. And he began to play Wagner’s Prelude to Lohengrin! I need not have worried about my ability to hear the performance. I could have heard it from Greenwich. It filled the whole of the South Bank. The electric drills stopped. Passing motorists on the Victoria Embankment swerved dangerously. Day-dreaming pedestrians started in wild surmise. And I, in fear of being apprehended from committing a public nuisance, sought sanctuary in my office…’.

Although the emphasis of humour in the concerts was manifest in the music itself, Gerard allowed his visual sense of fun full scope. A sedan chair, carried by four elegant bewigged pages in rococo uniform, was used to transport some of the more privileged participants onto the platform. Thirty-eight fanfare trumpeters from the Royal Military School of Music, in full regalia, brought visual as well as aural colour to the proceedings. One of the additional surprises arranged by Donald Swann in the Andante from the Surprise Symphony by Haydn was a dancer who wafted daintily across the platform. A large bouquet, indeed, almost a hamper, of vegetables was presented to the pianist Yvonne Arnaud, beloved actress, comedienne and musician, after her performance of the Concerto Populare.

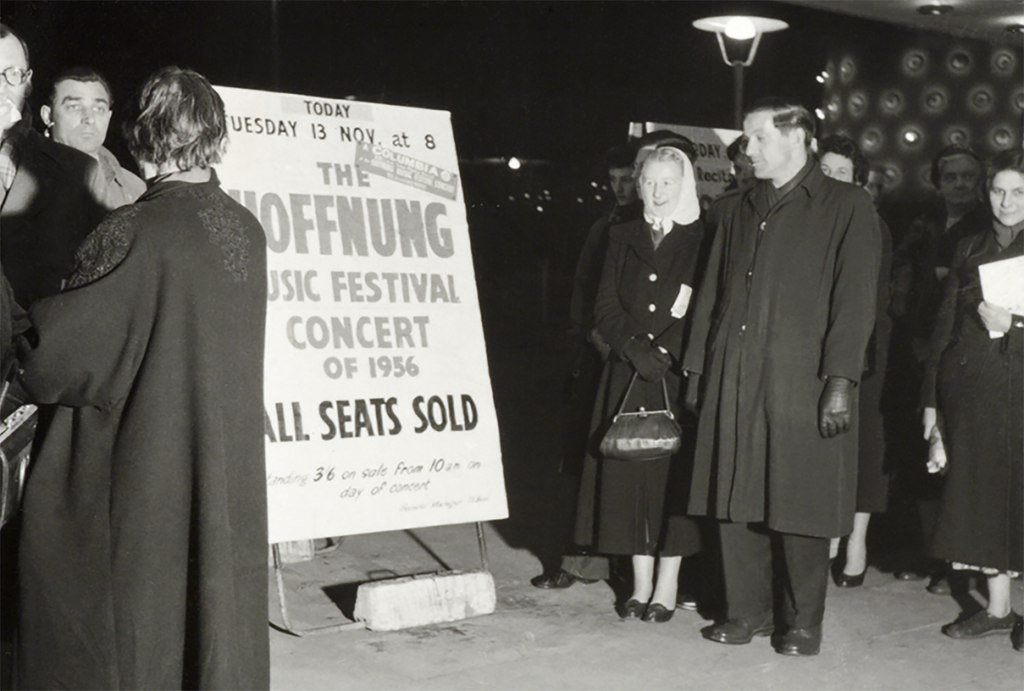

The public, by this time, anticipating that something rare, if not unique, was about to descend upon London, played their part, and when the Festival Hall Box Office opened, all tickets were sold out in under two hours, beating even the record of Liberace.

The BBC announced that they would broadcast the first half of the concert on television, and amidst frenzied activity events got further under way. Rehearsals were scheduled, and nervous tension increased as the day approached when the newly commissioned music would be heard for the first time. Sam Wanamaker the renowned stage and film director, our producer, remembers:

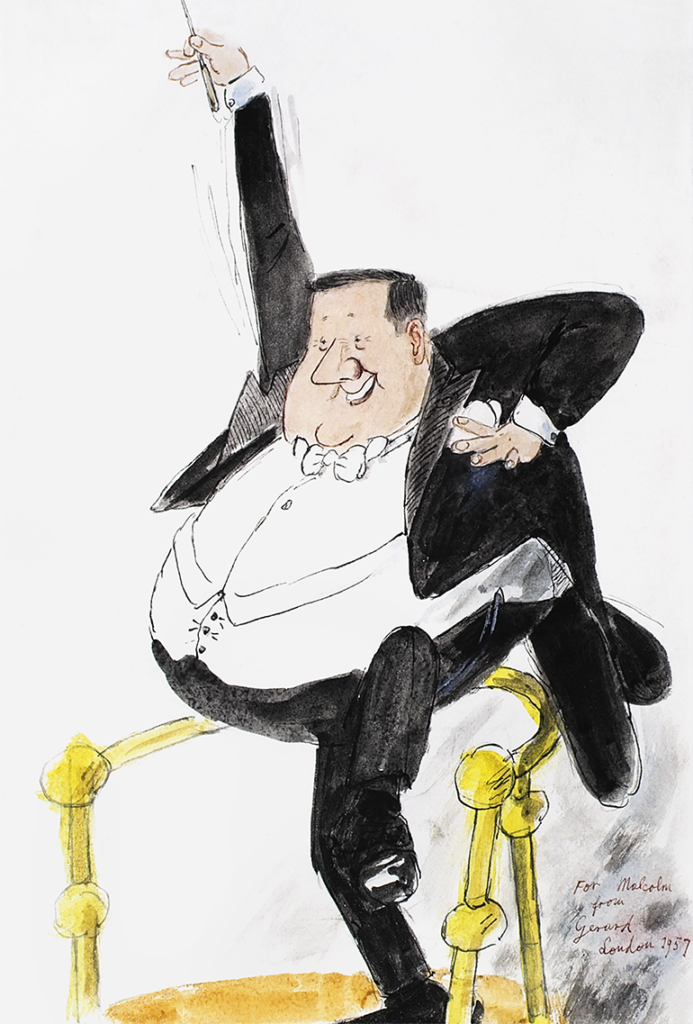

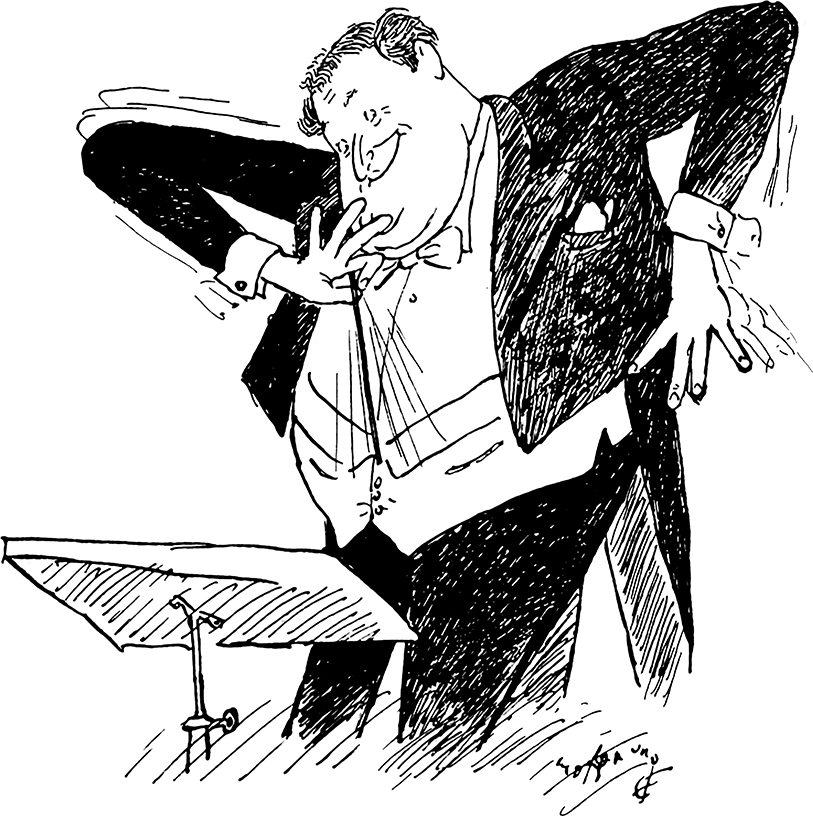

‘The first full rehearsal with Lawrence Leonard’s Morley College Orchestra was approached with a kind of controlled horror over the hoax we were about to perpetrate on an unsuspecting public. There was no turning back. Here we were, by now hundreds of people involved, driven by Gerard’s enthusiasm, and yet I had a strong premonition that it would all end in a terrifying shamble of amateur hijinks. The members of the orchestra sheepishly awaiting the start sceptically turned over the newly copied parts of Malcolm Arnold’s overture which he was to conduct himself. Gerard took his place beside his tuba smiling broadly. It may have been only my own anxiety which made me think his grin was too wide this evening. At last Malcolm mounted the podium to conduct his Grand, Grand Overture for three vacuum cleaners, a floor polisher, rifles and orchestra. He took up the baton and with a short ‘let’s have a bash’ raised the stick and gave the down beat. The impact of sound fairly lifted us all out of our seats. From time to time bursts of laughter from the non-blowing members of the orchestra greeted each audacious musical joke, nearly halting the wild flow as Malcolm flayed the air relentlessly.

At the end of the piece, with Malcolm supplying the noises of vacuum cleaners and rifles in the appropriate places, the orchestra dissolved into a convulsion of helpless laughter. I knew then that the Hoffnung Festival Concert was well on the way to becoming a unique and wonderful experience – whatever happened.’.

Many of us were not too sure, even after the dress rehearsal on the morning of the concert, that this would be so! It was the only rehearsal to be held in the Royal Festival Hall. In the allotted three hours, attempts were made to bring some order to the vast forces that were now congregated in the hall. Confusion and a feeling of quiet hysteria ran rife. We need not have worried. That night the vast hall exploded with mirth and the packed audience delighted in the evening of anarchic caricature. On arrival, there was no mistaking the festive atmosphere and the air of lively expectancy as a small military band in the foyer gaily piped a welcome to all comers. The audience, by now seated in the auditorium, sensed some measure of things to come as Ernest Bean made his brief announcement from the platform:

‘…Ladies and Gentlemen: owing to circumstances beyond the control of the London County Council and the management of this hall…’ – the audience drew an anxious breath – ‘…tonight’s concert will take place exactly as advertised…’.

He was closely followed by Sir Thomas Beecham in person, or so it seemed, who gravely perambulated across the platform to place a score on the rostrum – a brilliant, bewigged and be whiskered impersonation volunteered by a colleague, Ralph Nicholson. A critic pointed out a flaw in his performance – Sir Thomas’s habit of always bowing to the orchestra before acknowledging the audience.

A pronounced drumroll indicated that all should rise for the National Anthem – but that too was a leg-pull. Immediately the audience was dazzled by an army of fanfare trumpeters playing an irrepressible little fanfare by the British composer and double bass player Francis Baines. Malcolm Arnold, in the company of three solo vacuum cleaners and a floor polisher, made his appearance. A sudden interruption at the rear of the hall turned all heads in the opposite direction and revealed the violinist Yfrah Neaman as an improbable and most impressive virtuoso lunatic busker. He ran through the auditorium, hotly pursued by two attendants, wearing shorts, a baggy raincoat and hat, giving a bravura performance of The Irish Washerwoman.

Eventually, the audience settled down to more serious (sic) entertainment as A Grand, Grand Overture, dedicated to President Hoover, got under way. With its rich weeping melodies and the series of percussive climaxes in the endless, endless coda it did finally come to an end. As John Amis remarked in his programme note:

‘…If the nature of the coda seems cursory it must be remembered that Arnold always stops when he has nothing more to say…’.

Donald Swann, aware that Haydn had written a drumroll into the Surprise Symphony to wake up his somnolent audience, also knew that despite this disturbance they very quickly went back to sleep again. With this in mind he added a multitude of additional surprises to the andante in order to keep the audience awake and alert throughout. The performance culminated in a septet of stone hot-water-bottle players gently blowing their way through the final theme. Dennis Brain the legendary horn soloist, abandoned his French horn for the hosepipe in a special arrangement by Norman del Mar of Leopold Mozart’s Concerto for Alphorn and Strings.

The Times next day said:

‘Mr Dennis Brain played a concerto on a coil of rubber hose-pipe which emitted a faint but musical sound like a distant bugle call.’

Such was the enthusiasm of the players and the limitations of the budget that many willingly performed for the love of it. Dennis, after the performance, returned his cheque with a note.

‘Thank you so much for your letters and cheque, which I am returning as I think we arranged in the end that I should receive only expenses. These expenses, incidentally, amount to about half a dozen connections, to join together the various experimental pieces of hosepipe now lying somewhat festooned about the garden and are more than balanced by being allowed to play the first instrument in the Royal Festival Hall that I have not had to practise – the organ in A Grand Overture. My wife and I enjoyed the concert immensely and look forward to the next.’

Gerard, busily engaged throughout the evening as orchestral tuba player, was also soloist on several occasions. After his dissertation on the tuba (‘Ladies and Gentlemen, I have been asked by the London County Council to make an announcement about this tuba. This is a Stradivarius tuba…’)…

…he was joined by three fellow tuba players who together gave a rendering of ‘a nice delicate bit of Chopin’. He partnered Yvonne Arnaud in declaiming Sir Walter Scott’s ballad Lochinvar (set by Humphrey Searle for eight percussion players) and he played on the monster tuba in Gordon Jacob’s Variations on a theme of ‘Annie Laurie’, scored, in addition, for the contra-bass serpent (the only one in captivity, explained Gerard), and for serpent, two contra-bassoons, heckelphone, two contra-bass clarinets, two piccolos, harmonium and hurdy-gurdy -an odd collection of instruments for eye and ear.

Also performing were the Liverpool Chamber Music Singers under the lively conducting of musician humourist Fritz Spiegl. They declaimed Ernst Toch’s Geographical Fugue, and articulated place-names Honolulu, Titicaca, Mississippi with verve and precision. The highlight of the performance came when the conductor returned to the platform for an encore, to conduct the choir at breakneck speed as they frantically mimed their words to a speeded-up tape played off stage.

Orchestral Switch by Frank Butterworth was a sophisticated pot-pourri of forty-eight well-known themes so cleverly fused that some less musically initiated members of the audience could be excused for believing it to be one continuous composition. No one has yet won the prize offered at each performance for the complete list of works.

Gerard’s idea for a parody of the hostility that often exists between conductor and soloist on the concert platform was received with glee by Franz Reizenstein, composer of quiet genius.

The orchestra was to start with the opening bars of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1, only to be interrupted by the pianist determinedly making her entrance with Grieg’s Piano Concerto. There were ideas for ensuing battles until the final denouement when both would vie for the final chord. Rarely has musical conflict been expressed with such openness on the concert platform. Franz produced a work, brilliant and ridiculous, that continues to delight Hoffnung concert audiences throughout the world. Although Gerard decided to bring the concert to a close on a more serious note (Respighi’s Feste Romane), this was absolutely in keeping with the spirit of the occasion. One critic wrote

‘…the final carnival left one feeling that Berlioz and Quo Vadis were milk and water beside this Roman Festival…’.

With an orchestra of one hundred players and accompanied by the thirty-six royal trumpeters it fairly lifted the roof off the Royal Festival Hall. Observant members of the audience could discern Malcolm Arnold among the trumpets and Norman Del Mar among the horns. Yvonne Arnaud played the piano; Hugo Dalton played the mandolin and Dennis Brain was at the organ. Gerard was behind his tuba.

1956 PROGRAMME

A Grand, Grand Overture: Malcolm Arnold

Concerto for Hosepipe and Strings: Leopold Mozart

Concerto Populare: Franz Reizenstein

Andante from Haydn Surprise Symphony:

Arranged Donald Swann

Mazurka No 47 in A minor: Frederic Chopin:

arranged Abrams

Lochinvar for Speakers and Percussion with words

by Sir Walter Scott: Humphrey Searle

Variations on Annie Laurie: Gordon Jacob

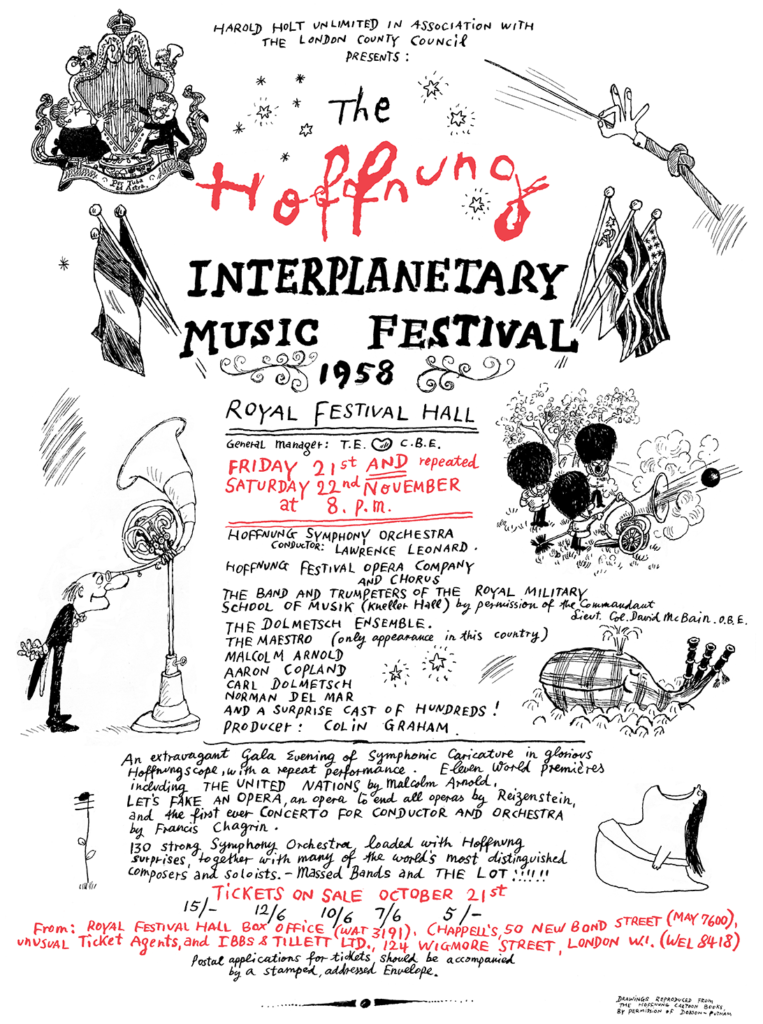

Following the success of the 1956 concert, in 1958 Gerard staged the Hoffnung Interplanetary Music Festival.

A short news clip taken by British Movietone during the rehearsal shows rare film footage of Gerard in action:

1958 PROGRAMME

Introductory Music played in the Foyer: Francis Chagrin

Hoffnung Festival Overture: Francis Baines

Metamorphosis on a Bed-time Theme:

Joseph Horovitz libretto Alistair Sampson

Sugar Plums: Realised by Elizabeth Poston

The Famous Tay Whale by William McGonagall:

Mátyás Seiber declaimed by Dame Edith Evans

A movement from Concerto for Conductor

and Orchestra: Francis Chagrin

Punkt Kontrapunkt ‘Bruno Heinz Jaja’ alias Humphrey Searle

Excerpts from The United Nations: Malcolm Arnold

Waltz for Restricted Orchestra: Peter Racine Fricker

Let’s Fake an Opera or The Tales of Hoffnung:

William Mann and Franz Reizenstein

Following Gerard’s death in 1959 a memorial concert was held in 1961. Recorded by EMI it was released in America on Angel Records 35828 and reissued by Hallmark in 2012.

1968

In 1968 a Hoffnung Concert was held in the Usher Hall at the Edinburgh Festival. James Loughran conducted the BBC Scottish Orchestra. The Amadeus Quartet were the distinguished vacuum soloists.

1969

On February 17, 1969, a Hoffnung concert was staged in the Royal Festival Hall in aid of the Notting Hill Housing Trust. It included some works from the 1958 festival and a new piece to celebrate Hoffnung; A Word from Our Founder by Malcolm Williamson. Conductors included Norman Del Mar and Dudley Moore with the New Philharmonia Orchestra.

1969 PROGRAMME

A Word from Our Founder: Malcolm Williamson

Metamorphoses on a Bed-Time Theme: Joseph Horovitz,

libretto by Alistair Sampson conducted by the composer

Sugar Plums: realised by Elizabeth Poston

Punkt Kontrapunkt: Humphrey Searle

Concerto for Conductor and Orchestra:

Francis Chagrin (conducted by Dudley Moore)

Let’s Fake an Opera, or, The Tales of Hoffnung:

Franz Reizenstein, libretto by William Mann

1988

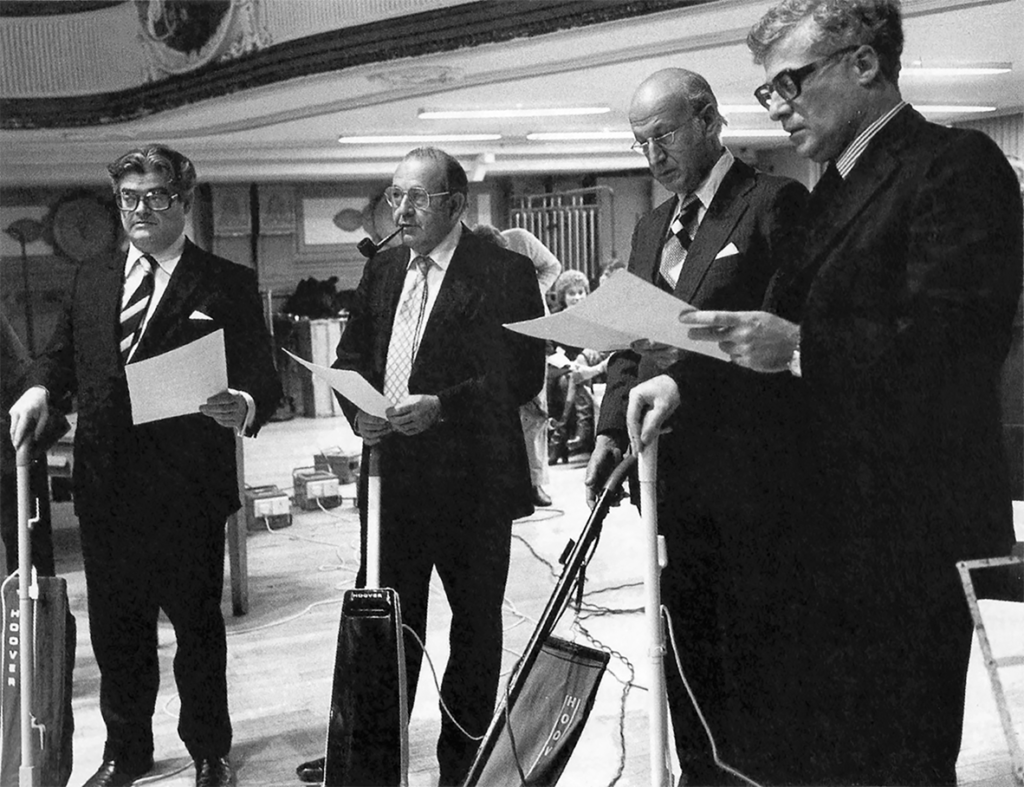

On February 12 & 13, 1988 two reprise concerts were performed and recorded at the Royal Festival Hall (released by Decca). The program, performed by the Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Tom Bergman, consisted of highlights from previous Hoffnung Festivals. Two new works by Wilfred Josephs were also added. Concerto d’Amore (for two violinists and one violin) and The Heaving Bagpipe. Annetta Hoffnung, Donald Swann and Gerard Hoffnung’s daughter Emily were among the distinguished guests who took part.

LATER CONCERTS

Following the ‘original’ concerts of the 1950s and 1960s, the 1970s and 1980s heralded a renaissance of concerts with further works commissioned. Produced by Annetta Hoffnung and Tom Bergman, performances were given in Europe, the United States, Canada, Japan and Australia.

Since the 1990s conductor Mark Fitzgerald, a keen proponent of the Hoffnung Concert genre, has staged a number of concerts, the most recent taking place in February 2020 in Reutlingen Germany.

The entire library of scores and parts are held within the Hoffnung Partnership archive.