GERARD HOFFNUNG

(1925–1959)

INTRODUCTION

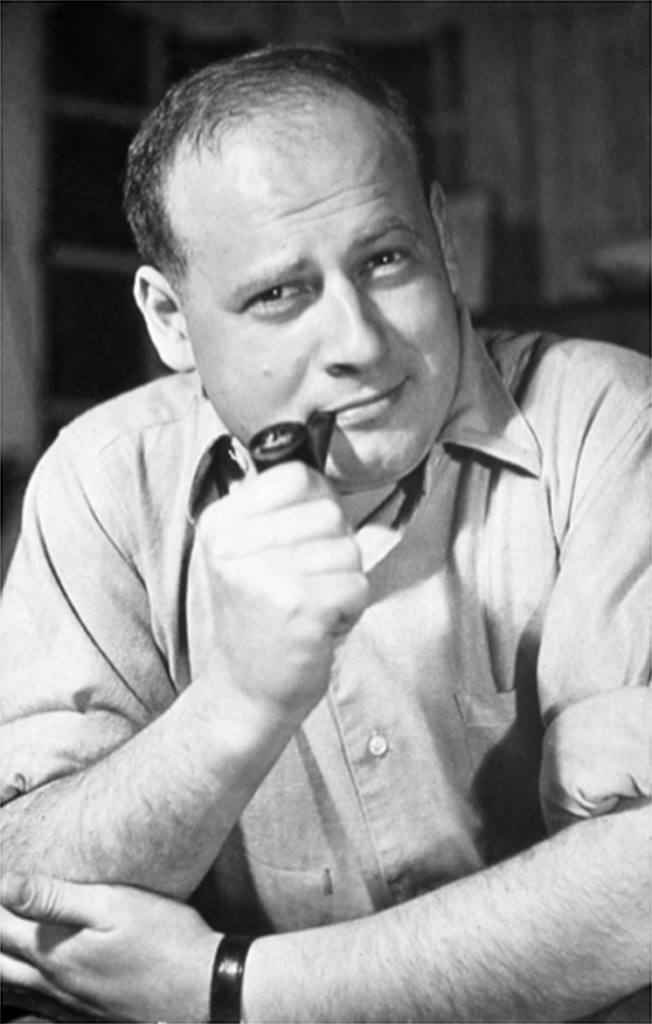

Gerard Hoffnung was an artist, musician, tuba player, humorist, broadcaster and raconteur whose work, even now, over sixty years after his death, continues to delight audiences around the world.

The following is taken from a talk given by his widow Annetta, an expanded version of which can be found in her book Hoffnung; His Biography.

Over the last nine years of Gerard’s life he produced most of the creative work for which he is remembered – hundreds and hundreds of drawings, mostly musical cartoons, illustrating his wonderfully absurd ideas. He devised and presented his own particular brand of symphonic caricature which burst onto London’s musical scene with his concerts at the Royal Festival Hall in the mid-1950s, and continued to resound around the world many years after his death. He also established himself as a broadcaster and raconteur, endearing himself to millions through radio and television and proving himself to be a much sought after speaker at the Oxford and Cambridge Unions. He fulfilled a lifetime’s ambition by acquiring a tuba and learning to play it, and his love of this instrument would become central to his life, a recurring theme in his performances and cartoons.

Yet Gerard was also a very serious person. When I first met him in the early 1950s, he was already a staunch campaigner against apartheid, and soon after that, he actively opposed nuclear armament. He became a Quaker and Prison visitor. There is more on these topics later on.

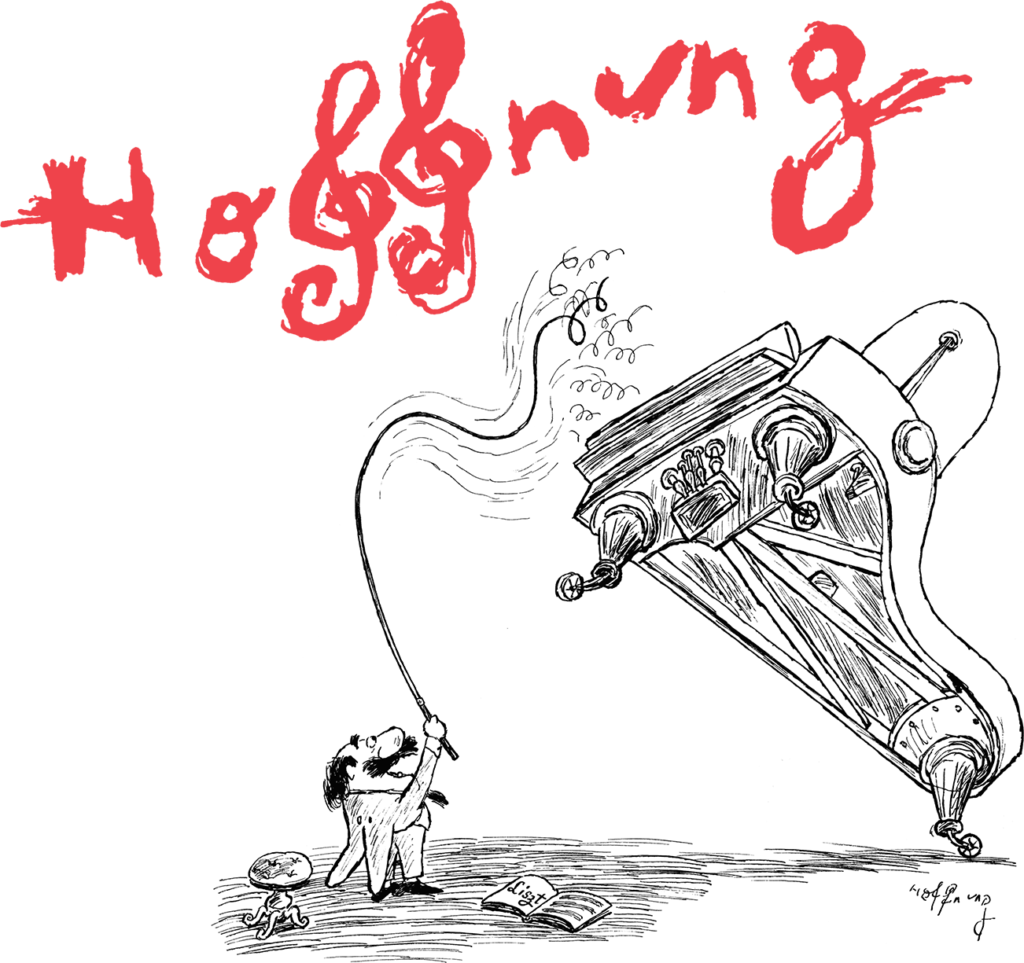

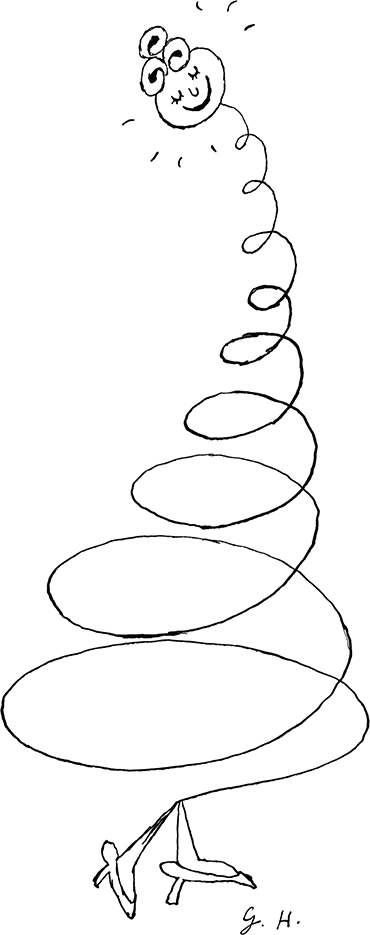

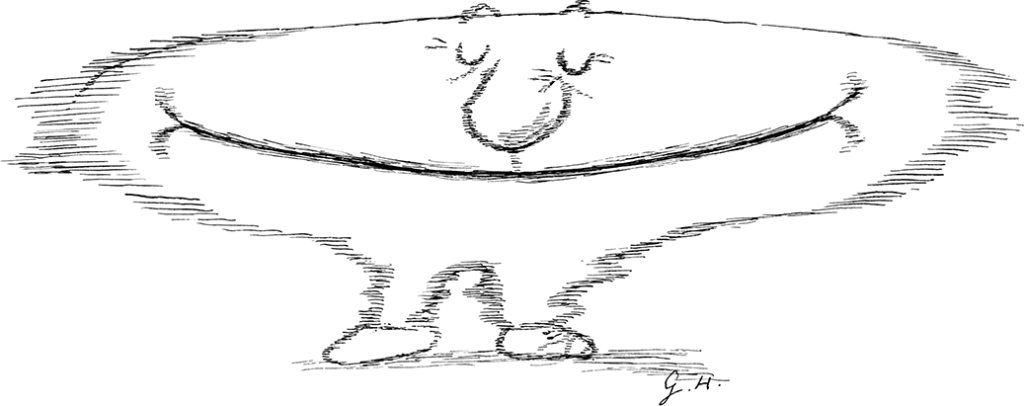

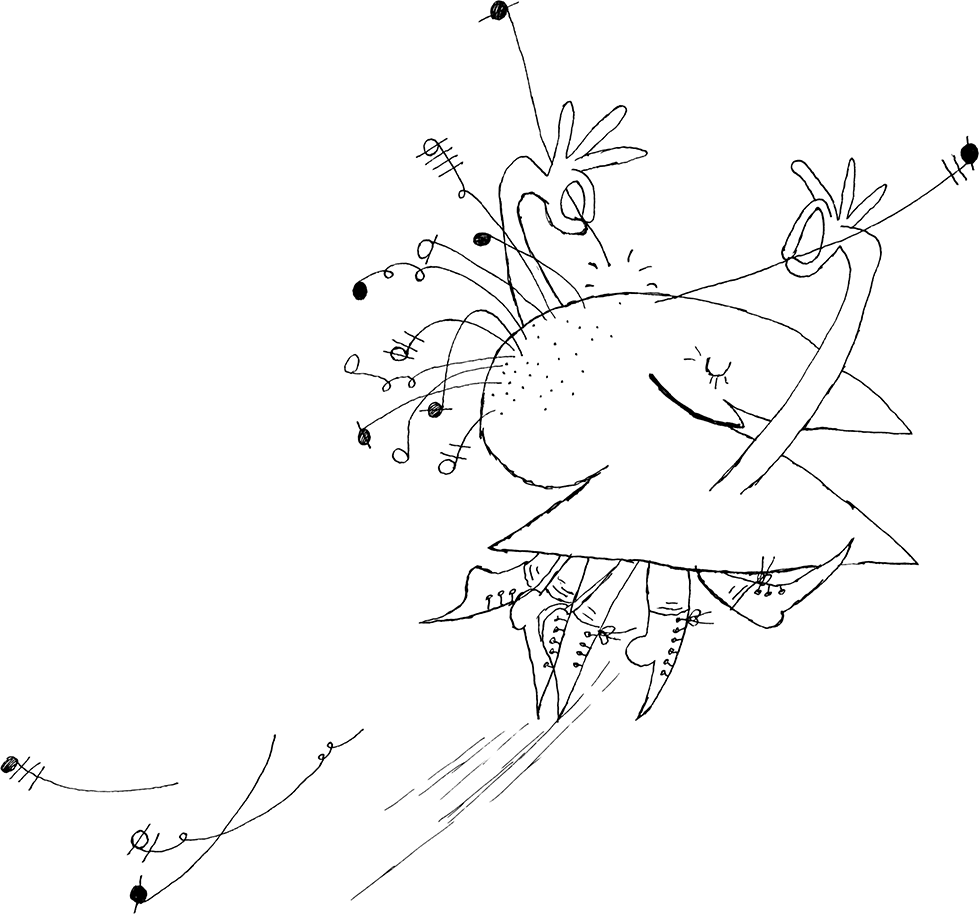

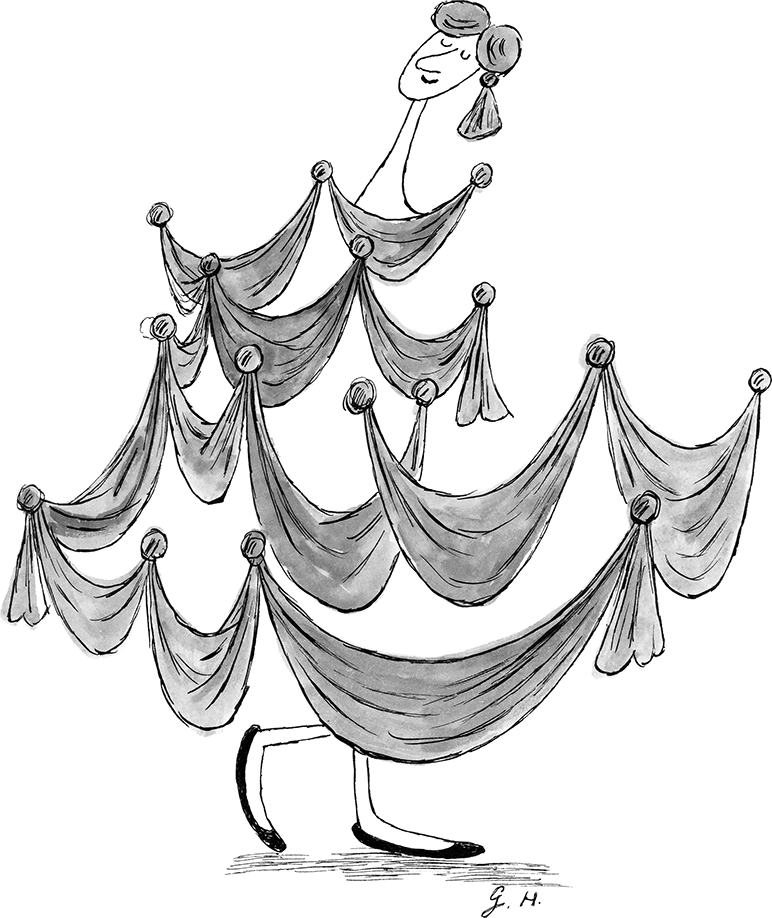

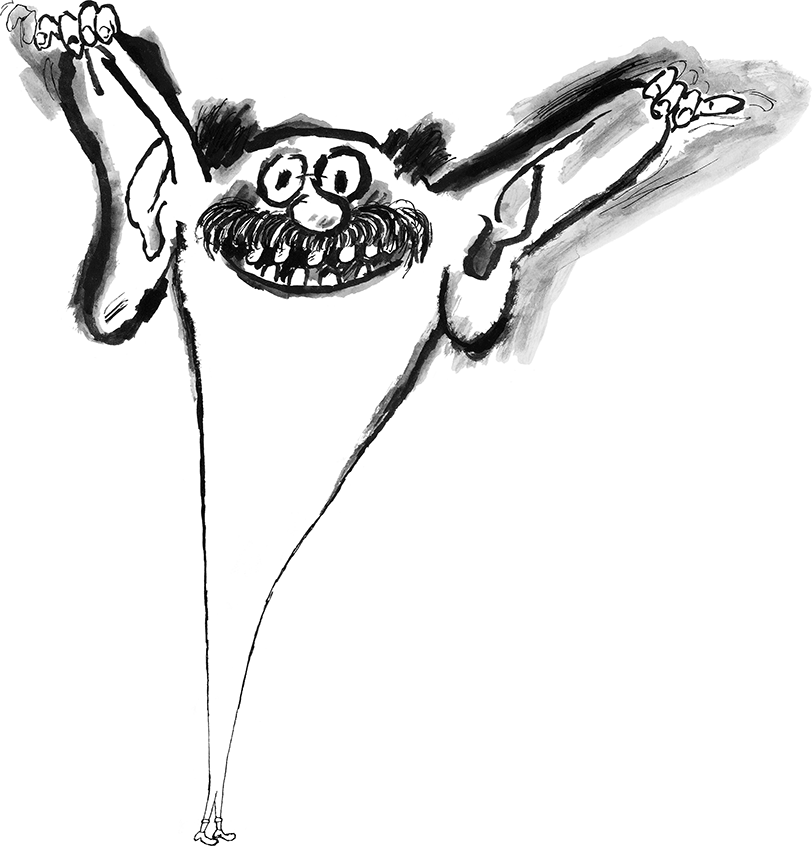

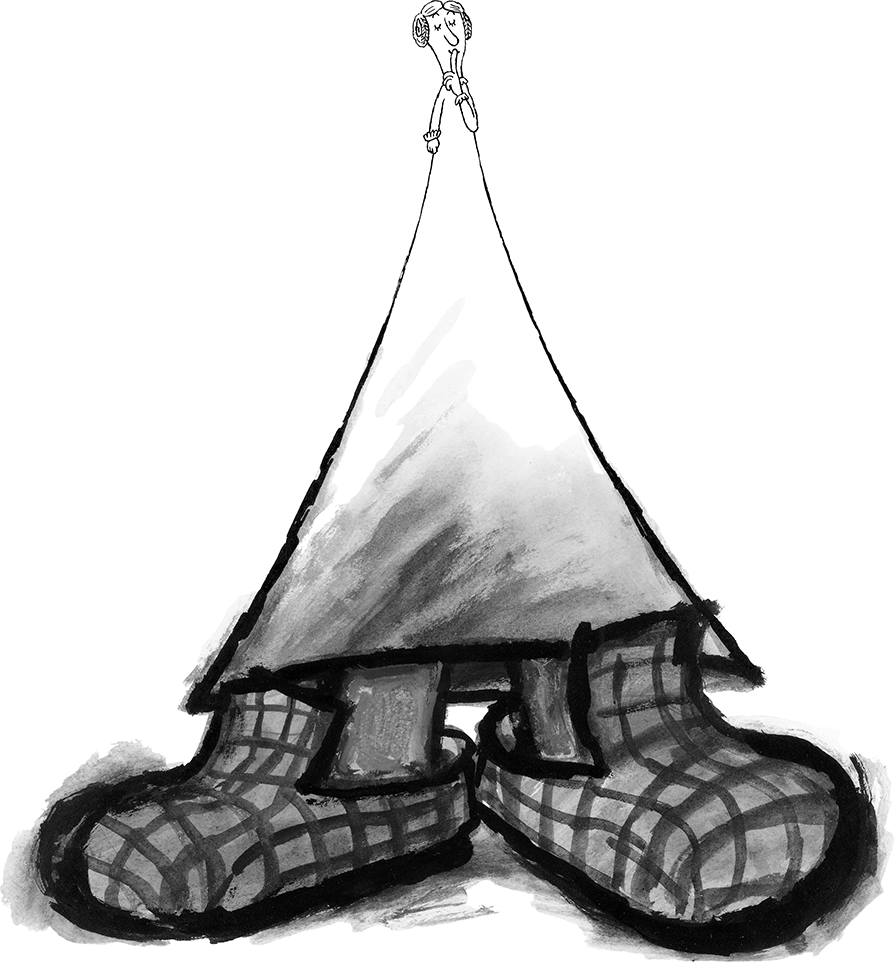

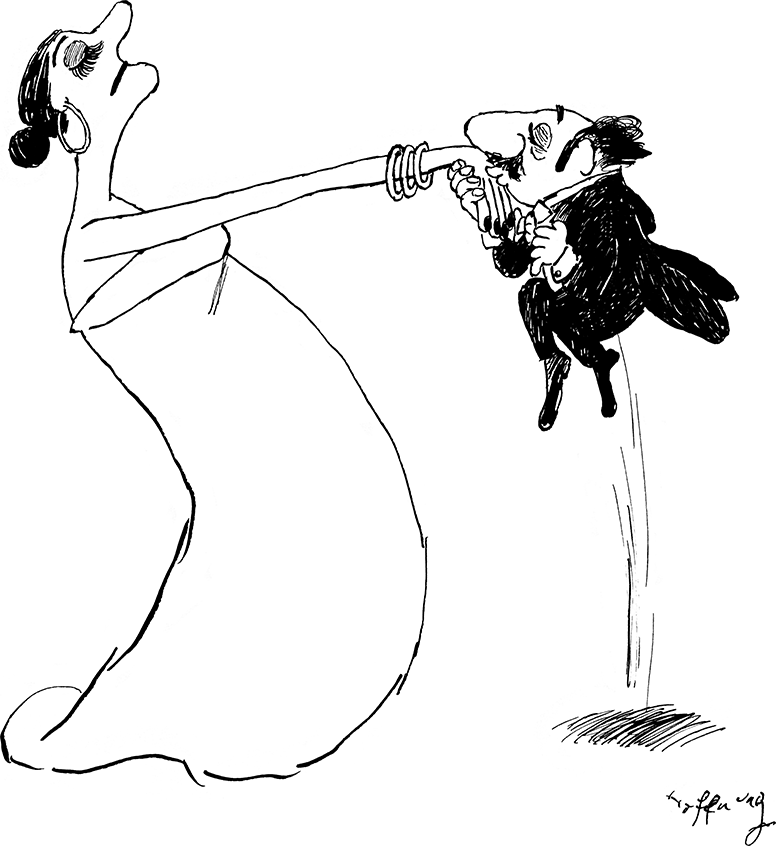

I always think that Gerard comes over best in his drawings and that, for all the rapturous response to the Hoffnung concerts, his particular contribution to the arts was the musical cartoon. Here are some that he did shortly before he died and I think they are among his most imaginative and tantalisingly far-reaching. They all depict musical sounds and of these drawings the music critic William Mann wrote that Gerard was on the verge of pure musical draughtsmanship and a completely unchartered artistic territory.

Early Life

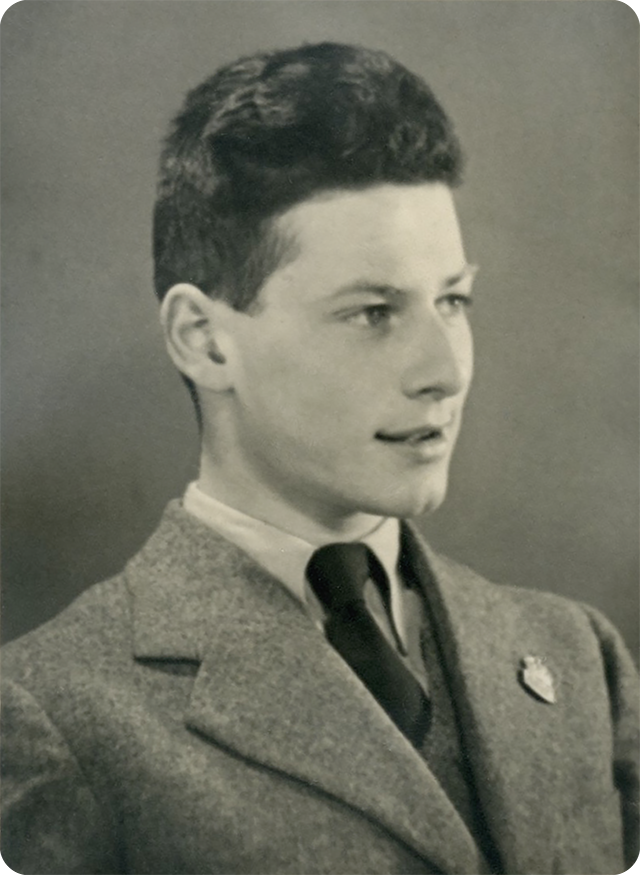

Gerard was born in Berlin in 1925, the only child of German-Jewish parents Hilde and Ludwig Hoffnung. Here you see him with his mother in a photo typical of the time.

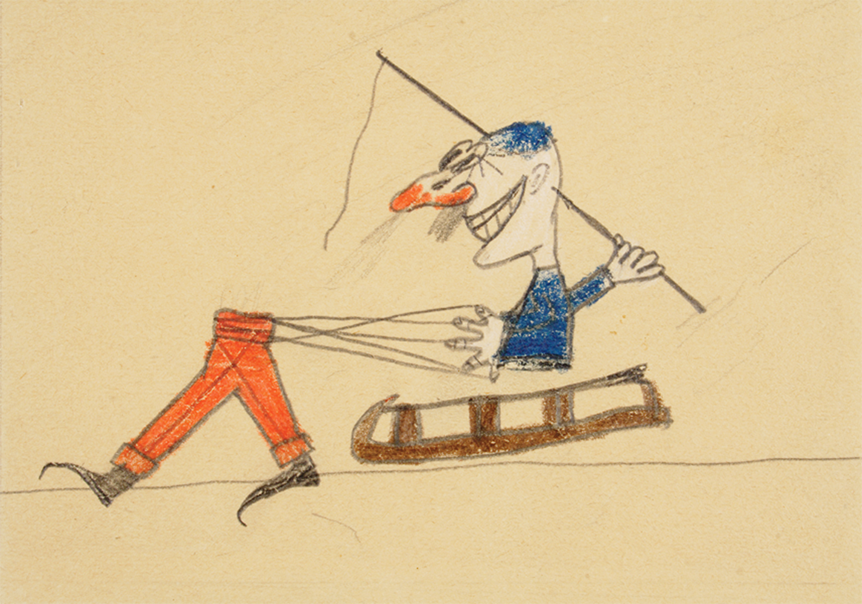

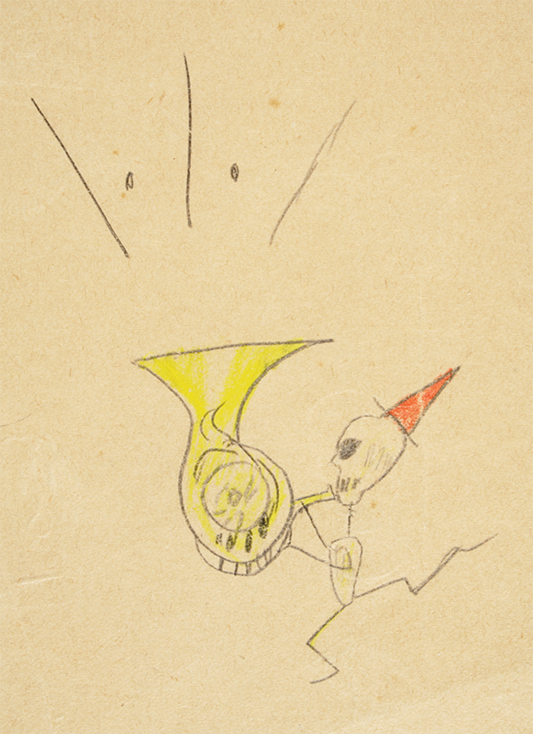

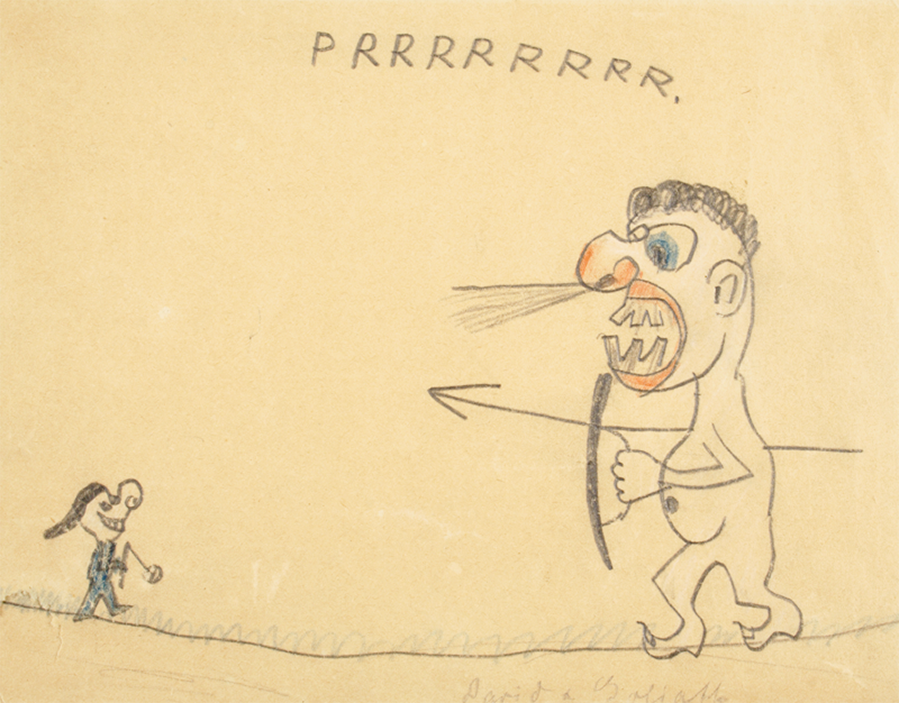

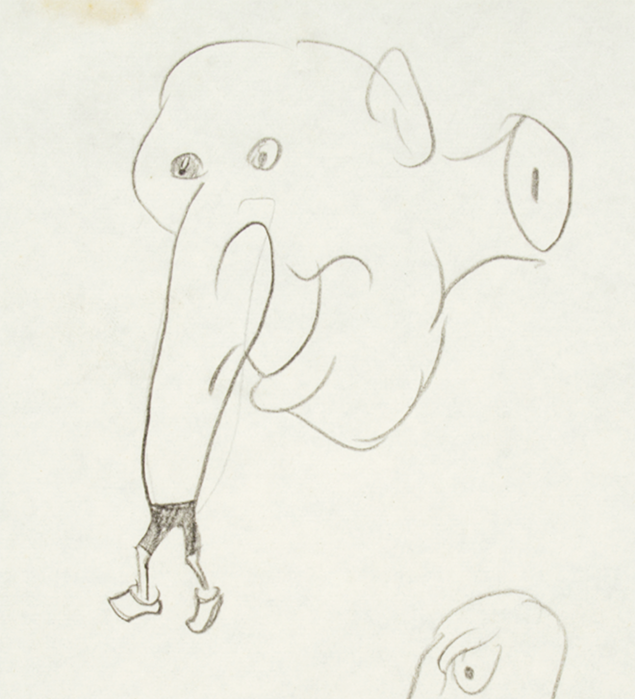

Hilde was a talented pianist and took a keen interest in the visual arts. She also sang, and Gerard would recall how, when he was small, she would sing and play her way through many of the popular operas so that this music became familiar to him while he was still in rompers. She read him fairy-tales and it was through these stories – the Brothers Grimm and the Greek myths and legends – that his imagination crystallized. A selection of his childhood drawings can be seen here, chosen from the many hundreds that survive, which were all carefully collected and dated by his devoted mother. Many of the drawings deal with humorous situations and some have a musical theme. Others show that before he was seven he was already familiar with many of the bible stories. Had I known my mother-in-law I could have asked her how it was that a small Jewish boy, albeit with a non-religious upbringing, became knowledgeable about the New Testament, Jesus Christ and the Crucifixion.

Although you see him here as a young boy with a saxophone, Gerard did not really have the temperament to learn to play a musical instrument. Indeed, he soon gave up the violin and his poor mother had to relinquish her fond hopes that the two of them might make music together.

Gerard attended a private kindergarten for non-Aryan children in Berlin, where education for Jewish children was becoming increasingly difficult in the 1930s. Despite its rather poorly equipped premises, the school had a first rate teaching staff and a headmistress of outstanding quality – Vera Lachman. Ironically, it was located next door to Himmler’s house. There’s a story of a football being kicked into the neighbouring garden, and of the uniformed guard on duty curtly refusing to return it when asked by Gerard. The following day, however, the ball was found lying in the school playground.

The Hoffnungs left Berlin in 1938. Their departure seems to have been made at very short notice, as this excerpt from a letter written by Vera Lachman to Gerard suggests:

‘… Yesterday I received a letter from your mother – please thank her very much for it. It says that you will not return to school. It is sad that we could not properly see each other before you left, but, maybe, it is better like that because it would not have been easy for either of us.

You know, Loki, that I have worried about you and was unhappy about many things: your inattentiveness and lack of discipline, your inability quietly to submit and fall in with others, your lazy unreliability, your secret love for anything that is deformed, tortuous and unnatural. But all the same I shall miss you, because I know that you are goodhearted and suffer with all those who suffer and that sometimes you hear the soft and secret beat of the all-pervading pulse of the world. I hope that your great gifts will bring joy to yourself and other people. I have often thought that deep down, Loki, we understand each other as if I were your older sister. I also know your fears: you never fear that anything could happen to you, but only that there is something frightening that exists. I also think I understand the fun you have in oscillating through the legs of all these dignified good men, who so seriously look over their paunches, and in poking fun at their dignified ideals. I don’t want you to become a waster, but to become an artist – that means work, work, work, work. I don’t want you to become a conductor or a designer but an actor. I tell you this today although it is too early, because I do not know whether we shall meet again. The diversity of your many gifts is a danger. You must decide on one route, otherwise you will fail. We will always miss you, Helmut most of all….’

The family travelled to Italy, where they lived in Fiesole overlooking Florence and Gerard was enrolled into the German School. For a short time it might have seemed that life was settling down but Gerard soon had to leave the school he was attending in Florence after Hitler’s decree that German schools were no longer allowed to accept Jewish pupils. An unpleasant episode then followed while Gerard’s father was away briefly in Palestine. Rumours abounded of a forthcoming plan of Hitler’s to visit Mussolini in Rome and of a decision to intern all Jews living in Italy. Gerard’s mother acted promptly and left immediately with him for the mountains. ‘…Good thing we left’, she wrote in a letter, ‘because they came looking for us…’. That this was a disturbing time for the 13 year old Gerard is made evident in another letter when she writes: ‘…I had to prepare Gerard for the possibility of internment and as you can understand, everything I have achieved is undone. Once more he is frightened, asks for his bedroom door to be kept open and the light left on. He is distracted and lacks concentration. I am upset about this…’.

I can imagine that it was these unnerving events that spurred her into further action. Late in 1938, again at very short notice, she and Gerard left Italy for England to join her sister who had emigrated to London a year or two before.

The Hoffnungs rented a house in Hampstead Garden Suburb and, for a short time, Gerard attended Bunce Court in Kent, where his uncle, the German art historian, writer and teacher Bruno Adler, taught art. The school had opened in 1933 and cared for German refugee children, many of whom had no other home at the time. Gerard proved to be his usual ebullient self and, after tolerating this for two terms, the headmistress Anna Essinger pronounced that he must leave. There was no disgrace attached to this decision; he received a warm welcome on the number of return visits he made to the school. Many years later, shortly after we were married, we lunched with Anna Essinger and her sisters, who were then living in Finchley, North London, and their affection for Gerard had not waned. Nor had their memories of his misdemeanors, which they related to me with glee.

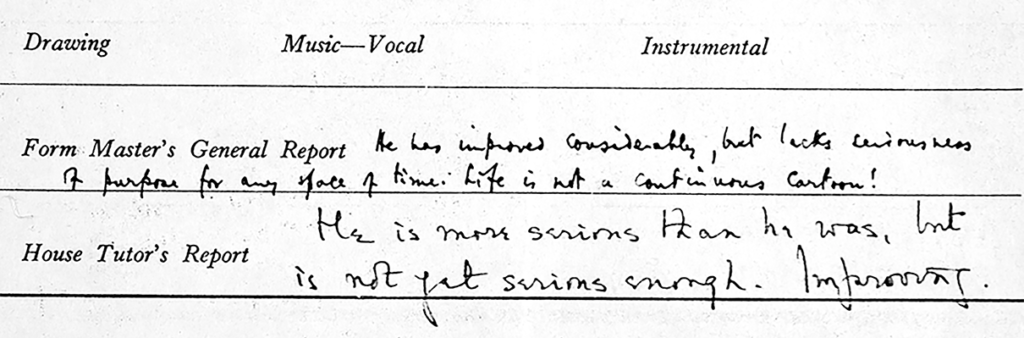

Gerard continued his education at Highgate School in northwest London. However, much to the regret of the other schoolboys – and, indeed, of the masters themselves – his mother was persuaded to take him away from the school because he was considered not to be making proper progress:

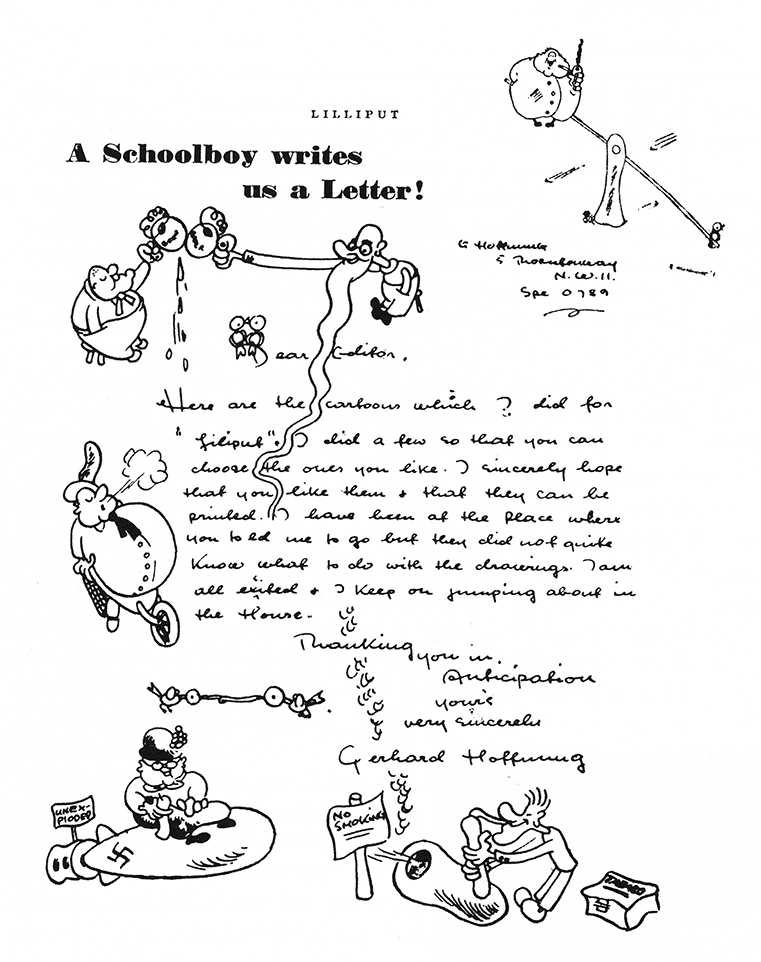

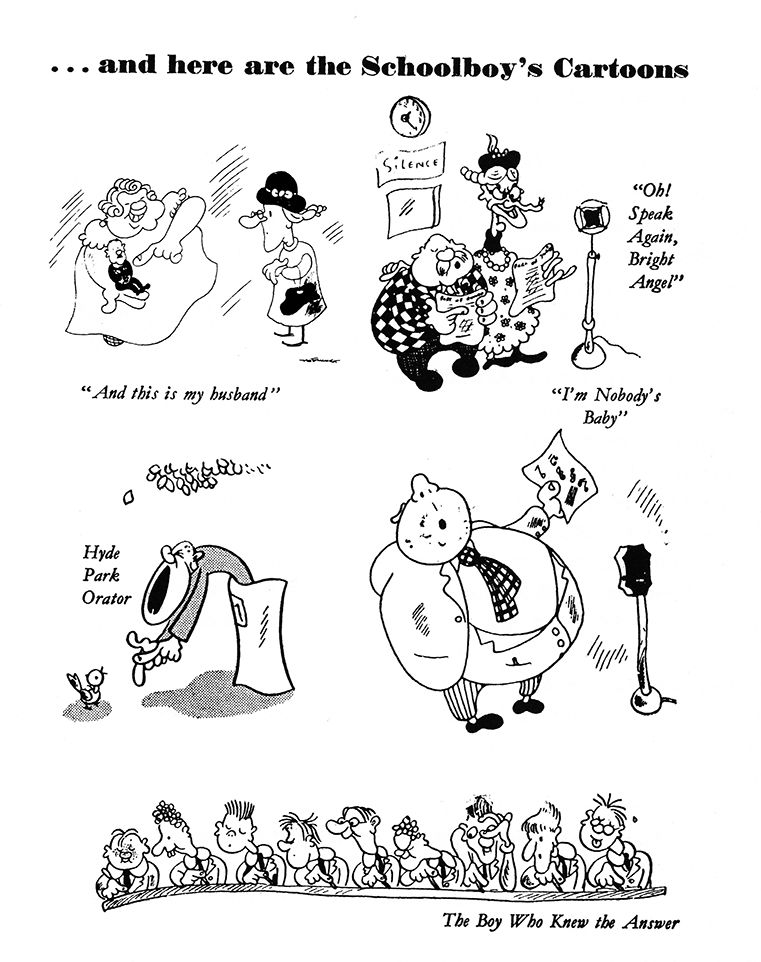

Yet, for all his masters’ regrets at his lack of seriousness, Gerard already knew the direction he wanted to take. Here he is, aged 15 and still at Highgate School, writing to the editor of Lilliput magazine, which published the letter along with its accompanying cartoons:

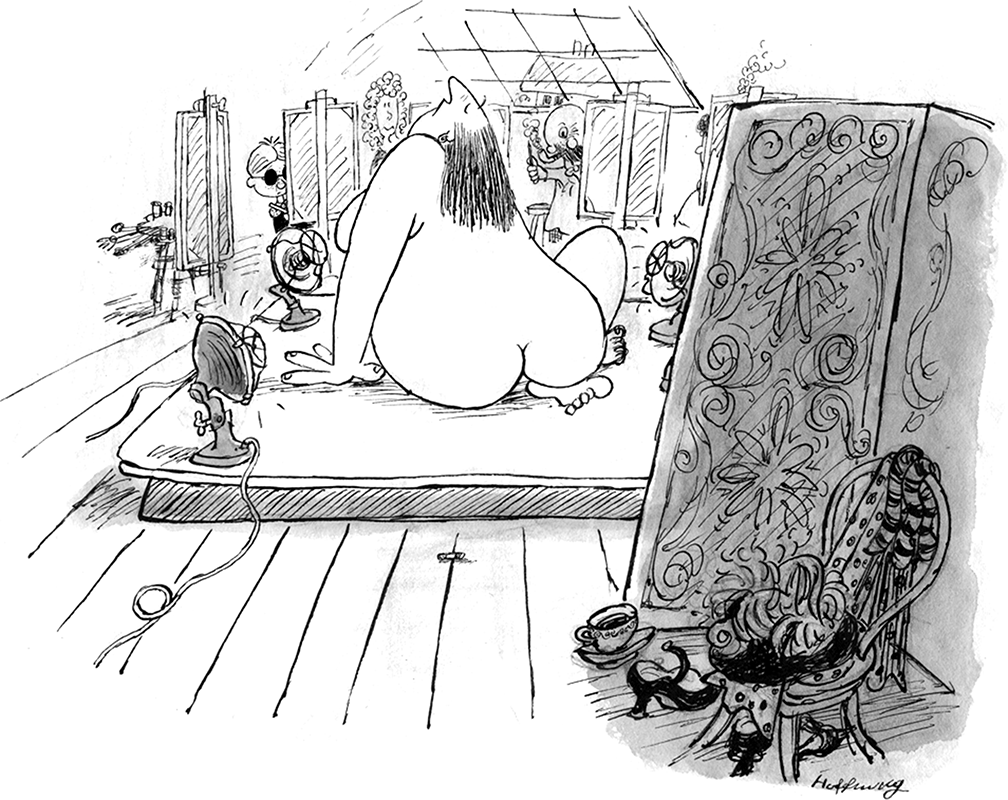

In 1942, Gerard attended Hornsey College of Art, from which he was expelled for refusing to take life classes seriously. This drawing, made several years after he left, was perhaps inspired by his memories of those classes. Fortunately, he found the head of Harrow Art College more friendly and sympathetic and his college years ended on a happier note.

He had just turned 20 when, in April 1945, he took a temporary post as Art Master at Stamford School in Lincolnshire, where his eccentricities endeared him to the boys. Colin Dexter, a former pupil who would later create the opera-loving detective Inspector Morse, and Gerard’s close friend Gerald Priestland, the former BBC Foreign reporter and Religious Affairs correspondent, elaborate here on Gerard’s unique and complex personality.

Early Adulthood

and Development as an Artist

After two terms at Stamford, Gerard returned home to live at 5 Thornton Way, his home in Hampstead Garden Suburb, from where he established himself as a freelance cartoonist, working for a number of magazines and newspapers. Soon his work was in wide circulation and was appearing in publications such as Lilliput, Housewife, The Strand, Tatler and other magazines. His drawings, carefree, kindly and gentle, brimming with life and humour, were received with special delight in the post-war restrictions and constraints of power-cuts and rationing.

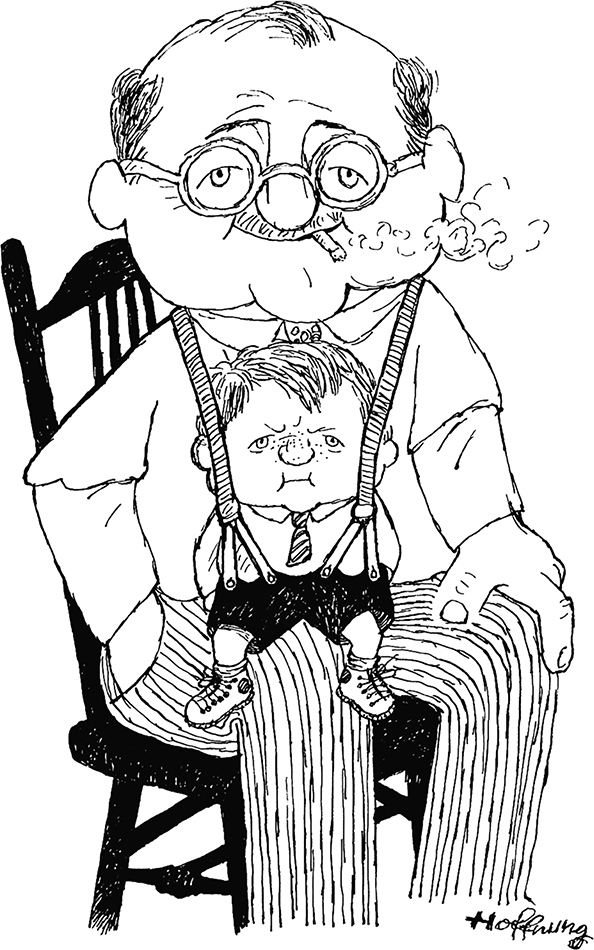

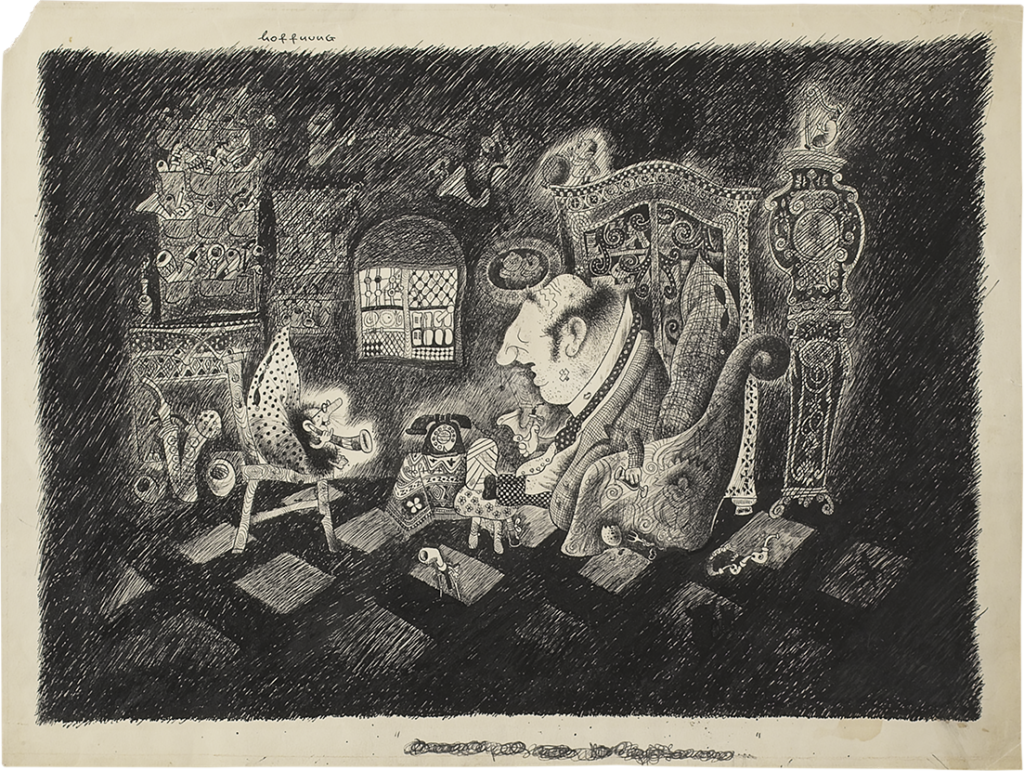

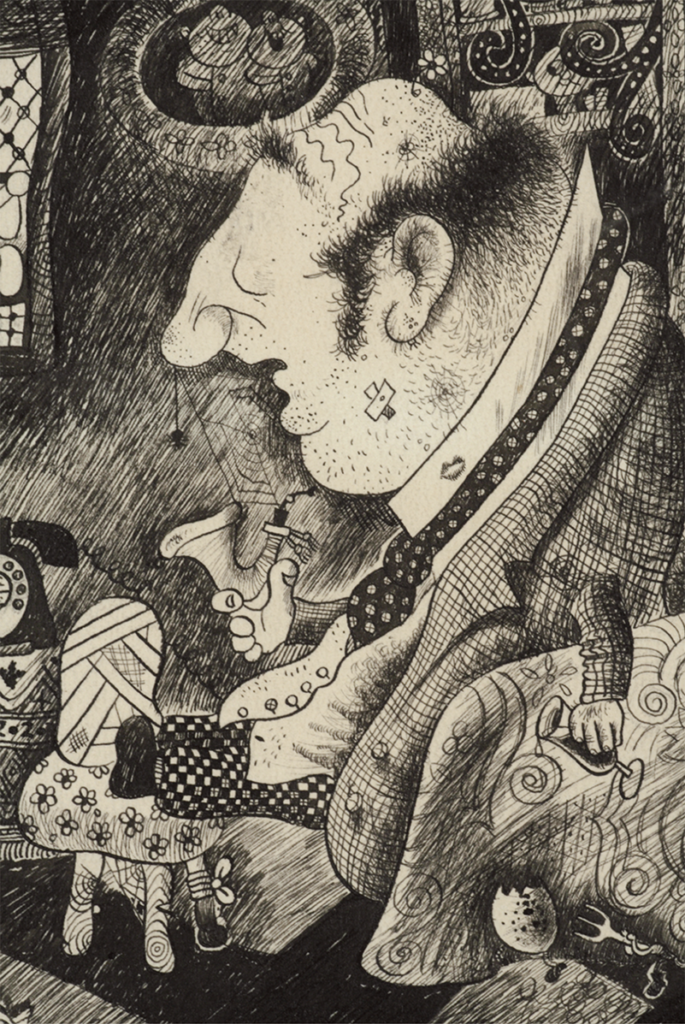

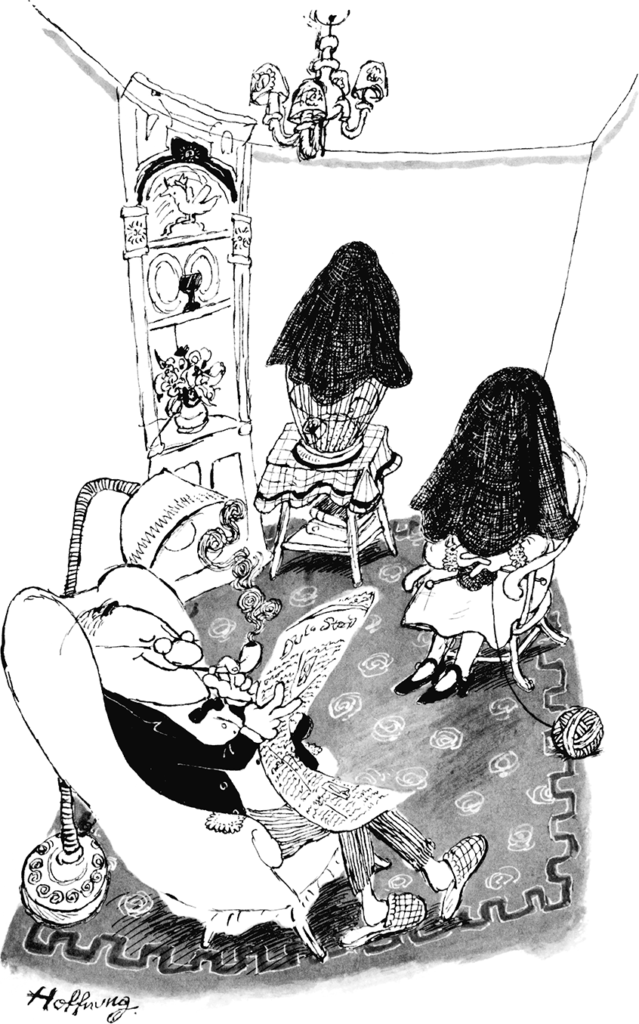

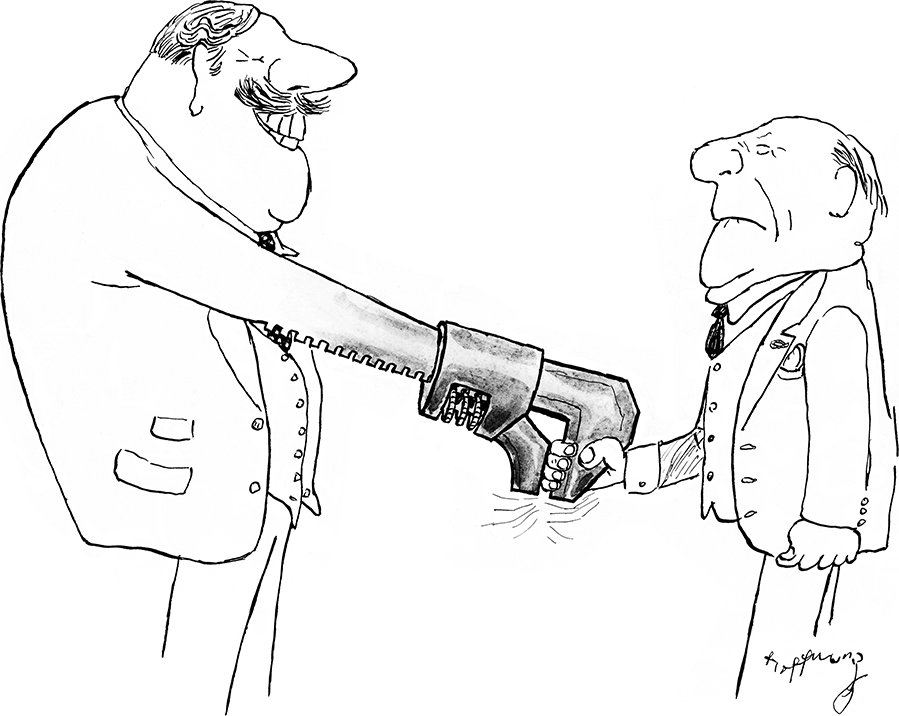

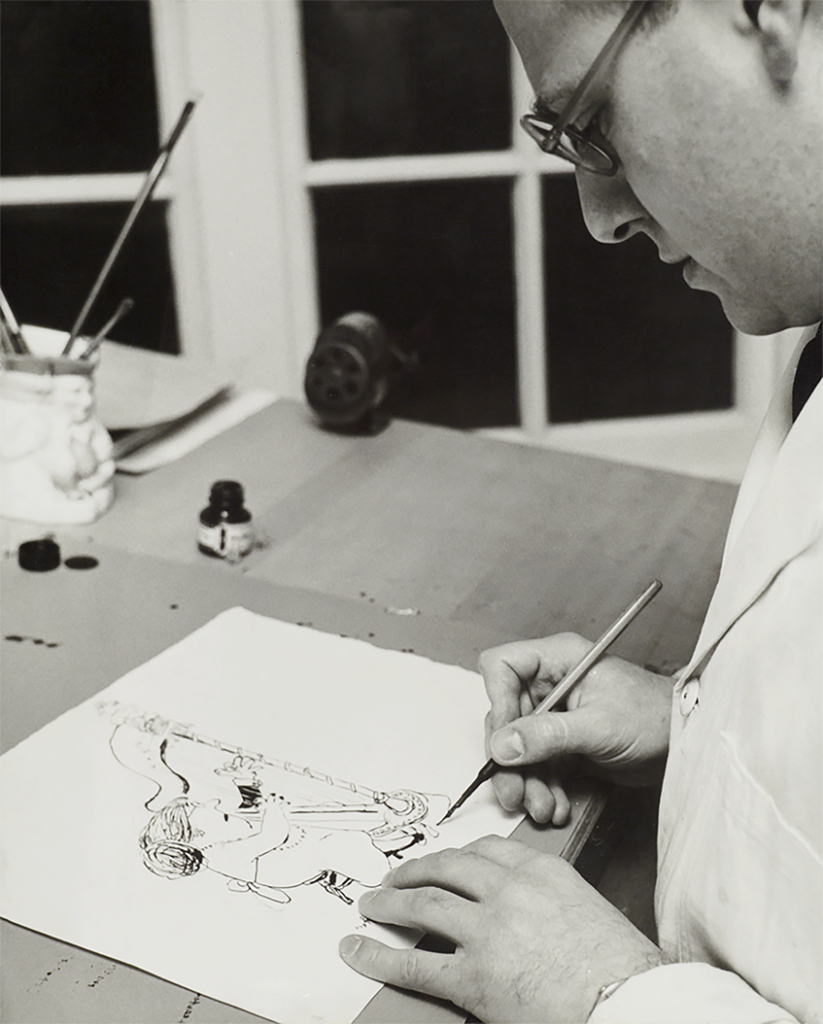

By the mid 1940s, Gerard’s style had begun to change. His drawings were no longer purely linear but became three-dimensional and packed with detail. Many were drawn in stark black and white, the detail scratched-in with pen and using lots of cross-hatching which created a striking illusion of depth.

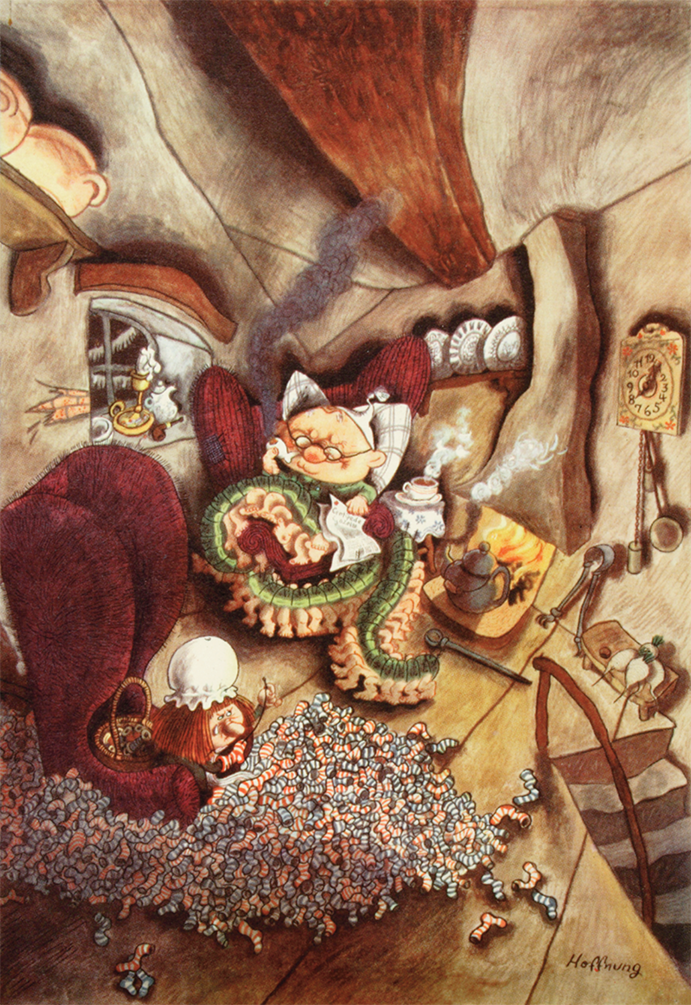

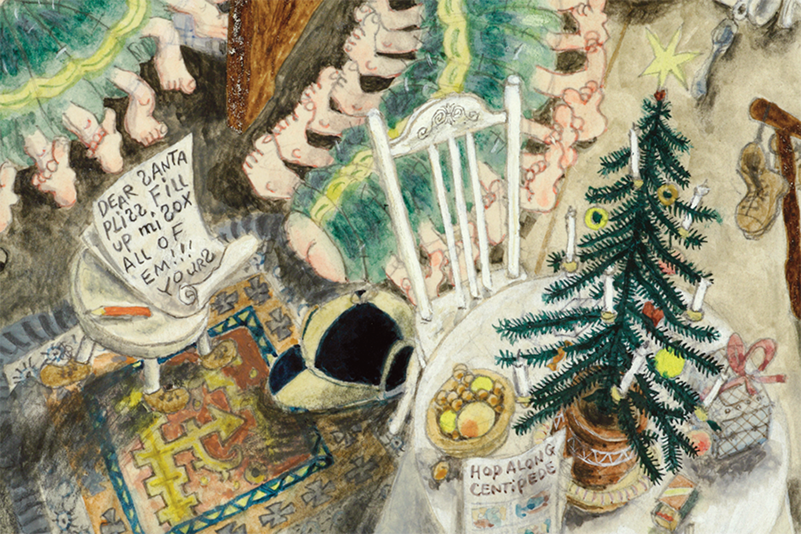

Around this time Gerard produced these two centipede-themed drawings:

To hear Gerard talking about these pictures click the link below:

As we approach the time of my appearance on the scene I should say a little about my background. I was born into a loving family in Folkestone, Kent, where my father ran an electrical business. At the outbreak of the second world war, he joined the Home Guard. As a schoolgirl, I was evacuated to Merthyr Tydfil in South Wales and later served with the Wrens for four years.

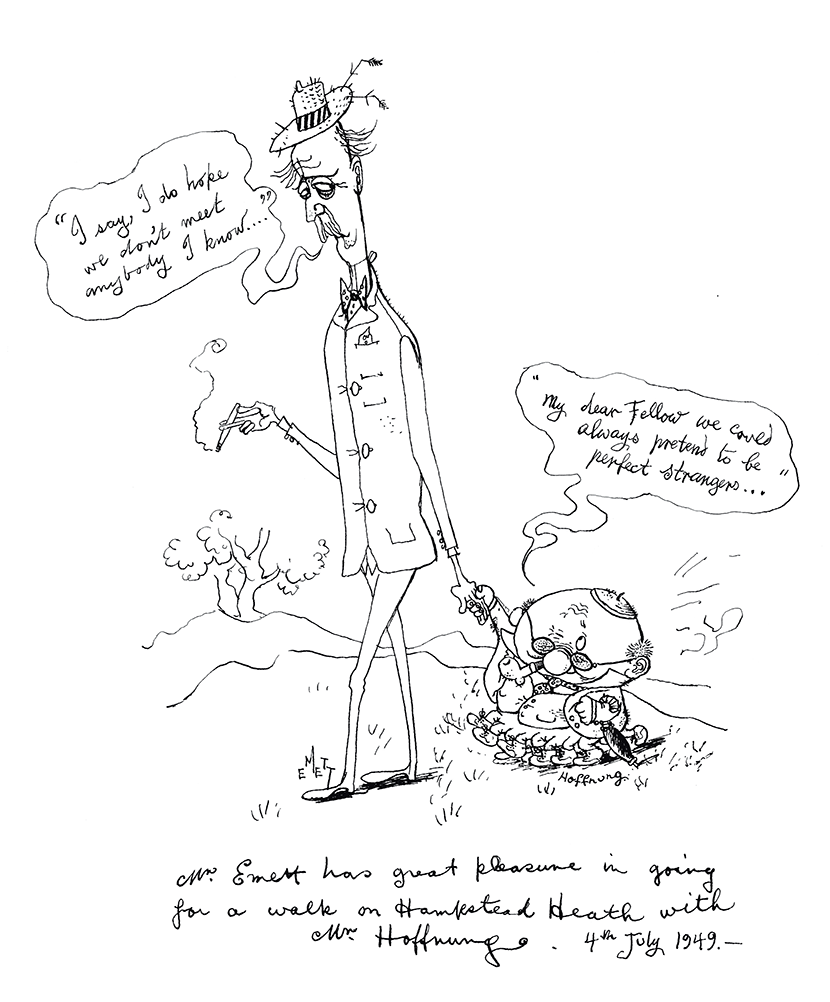

After the war ended, I trained as a Norland nurse, and in 1948 took a post looking after the daughter of the Punch cartoonist Rowland Emett.

Gerard greatly admired Rowland’s work and here is a drawing made by the two of them just after they’d been for a walk on Hampstead Heath.

I moved on to work abroad for a year but, returning to London from Ireland on a break, I visited the Emetts for dinner. The other guest was Gerard Hoffnung. I remember very clearly the moment of his arrival that evening, there was a discreet tapping and from behind the door there appeared a round and beaming face. His complexion was fresh, his eyes blue, his hair sparse and his shape portly. I mistakenly judged him to be in his mid forties, in doing so fell into a common error. He was in fact twenty-four years and ten months, just nine months younger than myself. I was immediately fascinated, intrigued and enchanted by this curious man who kept us entertained with his absurd stories and mimicries, yet who would suddenly become serious over matters that concerned him. During the next three weeks we saw each other almost every evening, however I had to return to Ireland and Gerard was preparing for a forthcoming visit to New York where he would be for several months. It became apparent that this was an unhappy time for both of us.

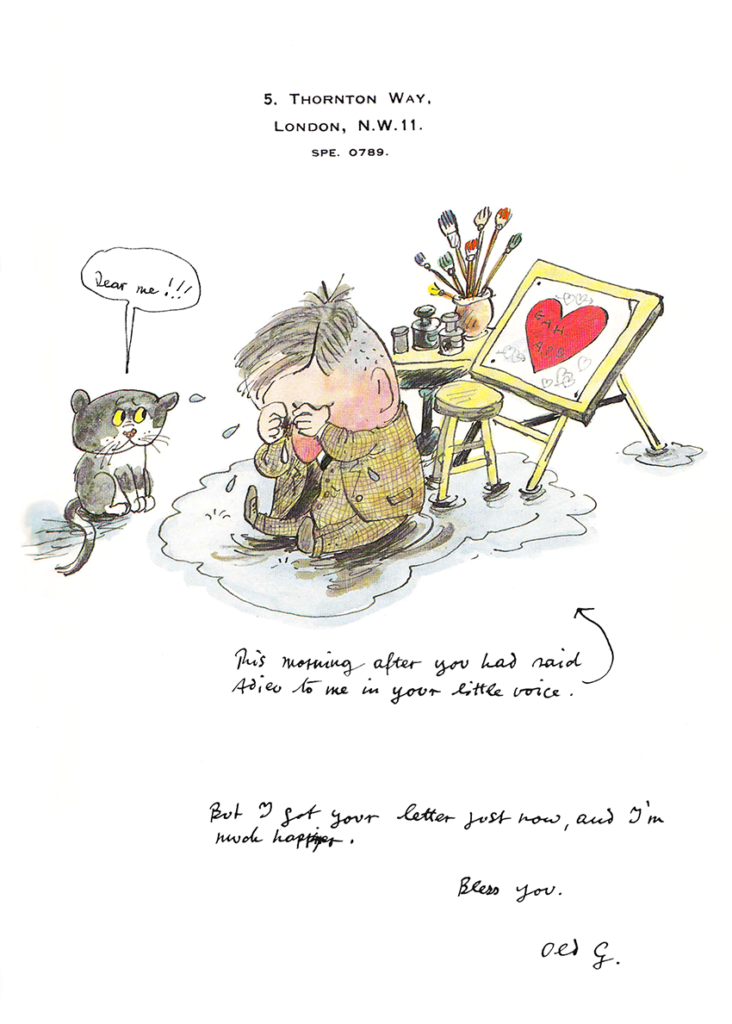

Over the next few years we continued to write when we were apart and when we were both in England we would spend all our time together, eventually marrying 1952.

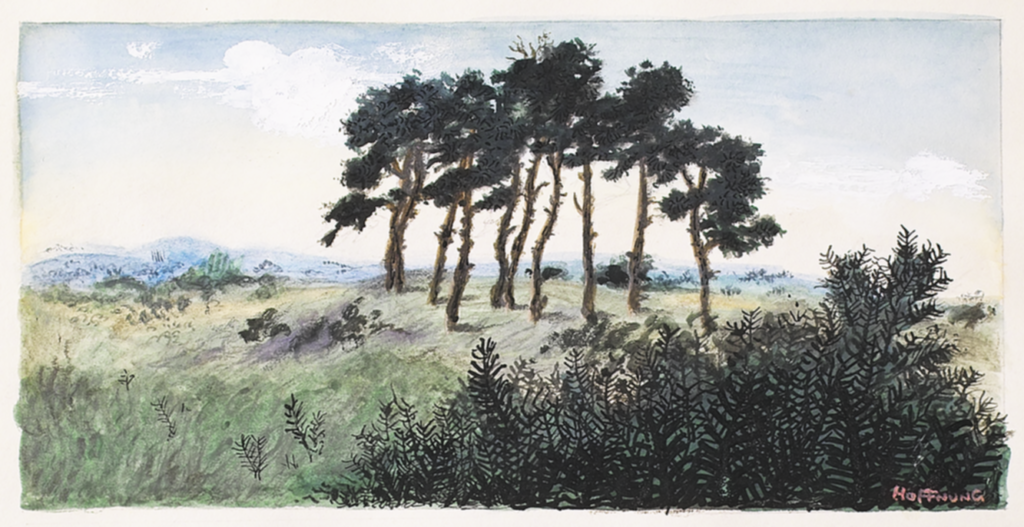

Here is one of the few serious paintings that Gerard did around this time: a study of a group of trees on Hampstead Heath.

Gerard as a Raconteur

At this time Gerard’s career continued to gather momentum. A talk submitted to the BBC in 1950 was accepted and marked his first public success as a raconteur. Entitled Fungi on Toast, it was subsequently published in The Listener, his first contact with his listening public.

At much the same time a chance encounter took place between Gerard and Ian Messiter, creator of Radio 4’s One Minute Please (later to become Just A Minute). So struck was Ian by the idiosyncracy of Gerard’s manner that he asked him to take part in the programme. Bruno Adler wrote at the time:

‘…So began a new phase which was not confined to drawing. The radio revealed him as a natural comedian, both in his talks and in his activity as a member of the quiz programme One Minute Please. This really brought him the wide popularity which turned him into a national personality. What he said and the way he said it were just as oddly absurd as his drawings, turning logic inside out and reason upside down…’.

Another favourite was a radio programme called Saturday Night on the Light, where Gerard was interviewed each week on a variety of subjects by Charles Richardson.

Quite a different challenge confronted him in 1952 when he was invited to speak at the Cambridge Union. Alastair Sampson, who was president of the Union at the time, described the occasion of Gerard’s visit:

‘…Gerard came and gave one of the most superb comic oratorical performances that the Union can ever have heard. Devoid of cruelty and vulgarity, it was a superb example of pure humour. He was enchanting, fascinating and tumultuous. One moment he was offering snuff to his undergraduate audience, the next he was touching the microphone and leaping back as though electrocuted…’

During the ensuing years he made three further visits. The University newspaper, Varsity, wrote ‘…He was funnier than anyone has been at the Union before…’.

The last Union debate Gerard spoke at was his first at Oxford. Good fortune attended us all when the BBC decided to record the Oxford Union Debate on Thursday 4 December 1958 (it was the only debate at which Gerard spoke to be recorded). ‘Life begins at thirty-eight’ was the motion. Gerard told, amongst other stories, the Story of the Bricklayer which soon became, and remains, one of the most popular pieces of Hoffnung lore. The story itself is as old as the hills and can be traced back to 1926 and Gerard found this particular version in the Manchester Guardian. He cut the piece out, folded it neatly into his wallet and carried it with him in his breast pocket. At the slightest opportunity he would draw it out decorously and declaim it to his friends and acquaintances. The fact that the more he told this story the more he enjoyed it, and the more often people heard it the more they enjoyed it too, must, I think, have something to do with the law of comic dynamics, the tantalizing fun of waiting for the final denouement. This story gave Gerard full scope for his love of heightened drama and his sense of timing. He obviously relished every moment of it.

Domestic Life and Cartoons

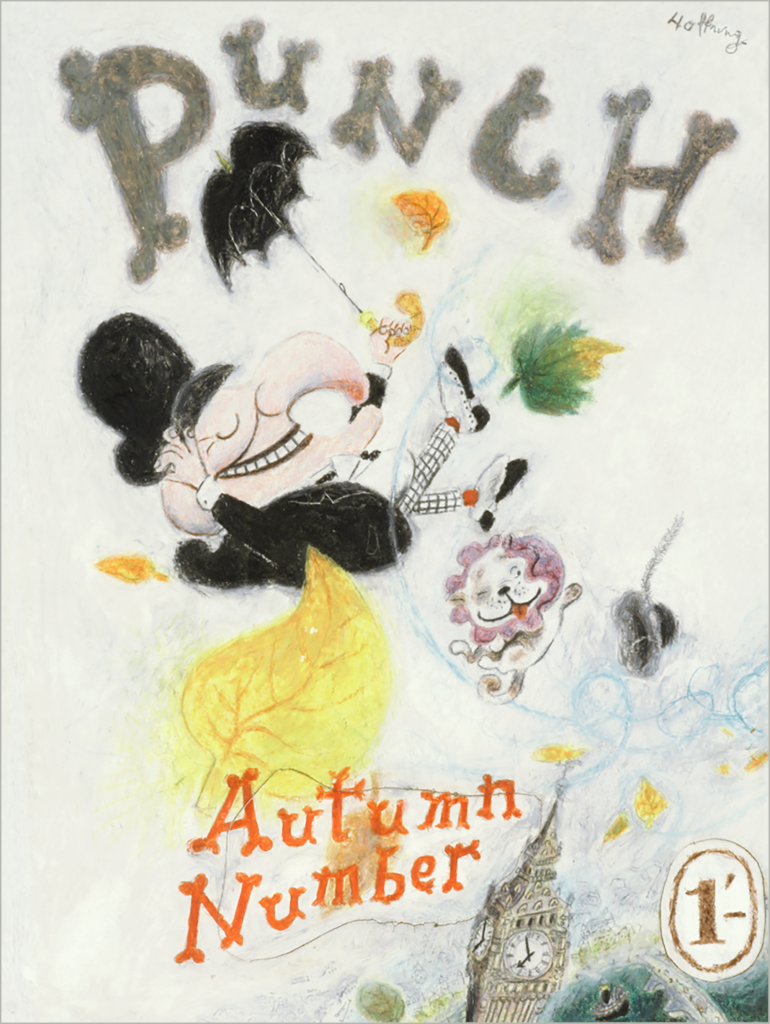

In 1952, another exciting thing happened: Gerard had his first drawing accepted by Punch. Here it is, along with several others that also appeared in the magazine.

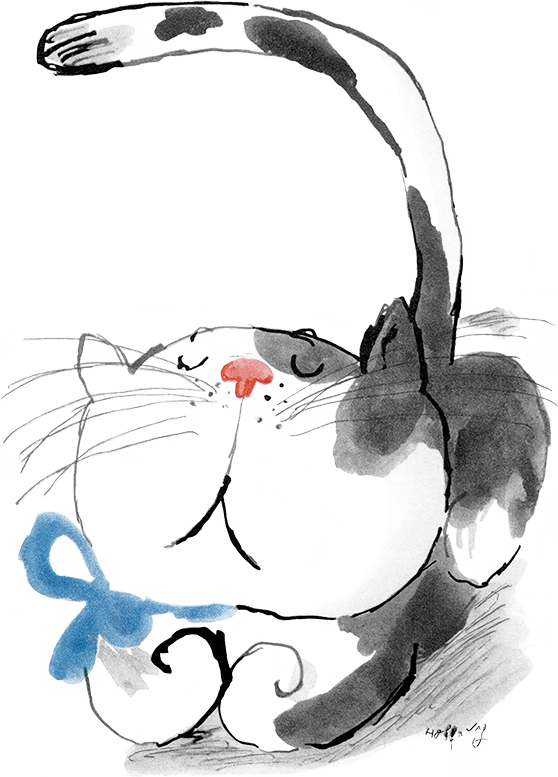

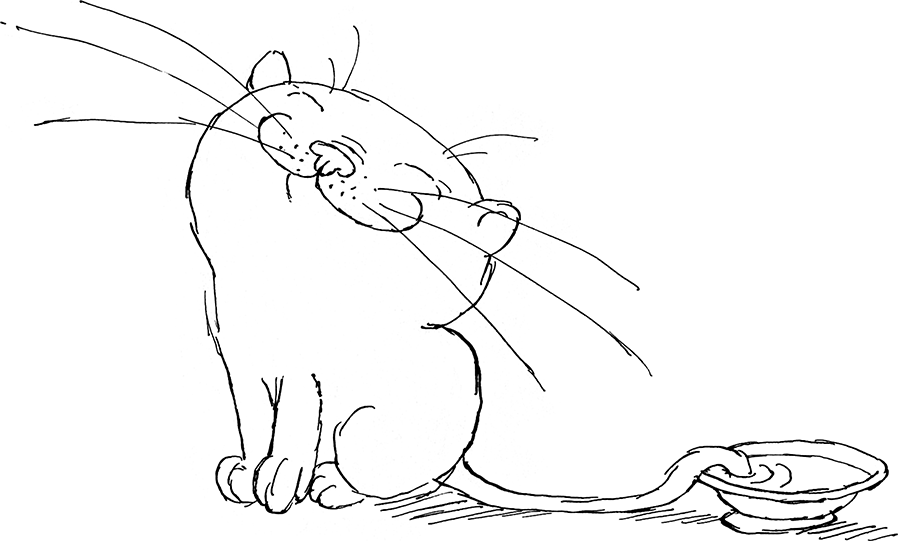

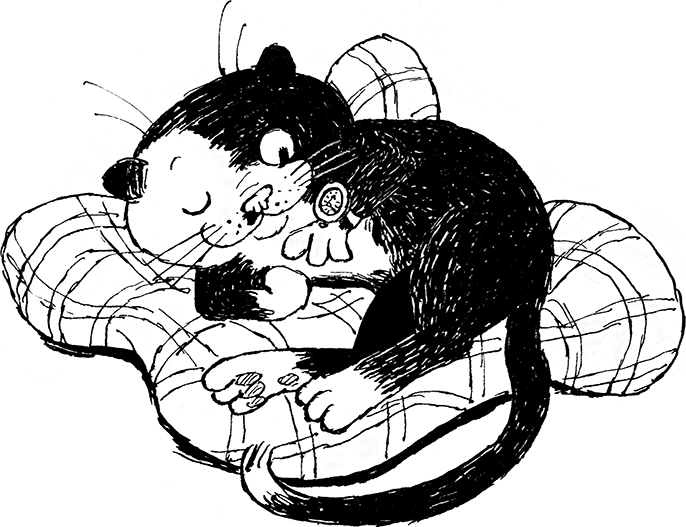

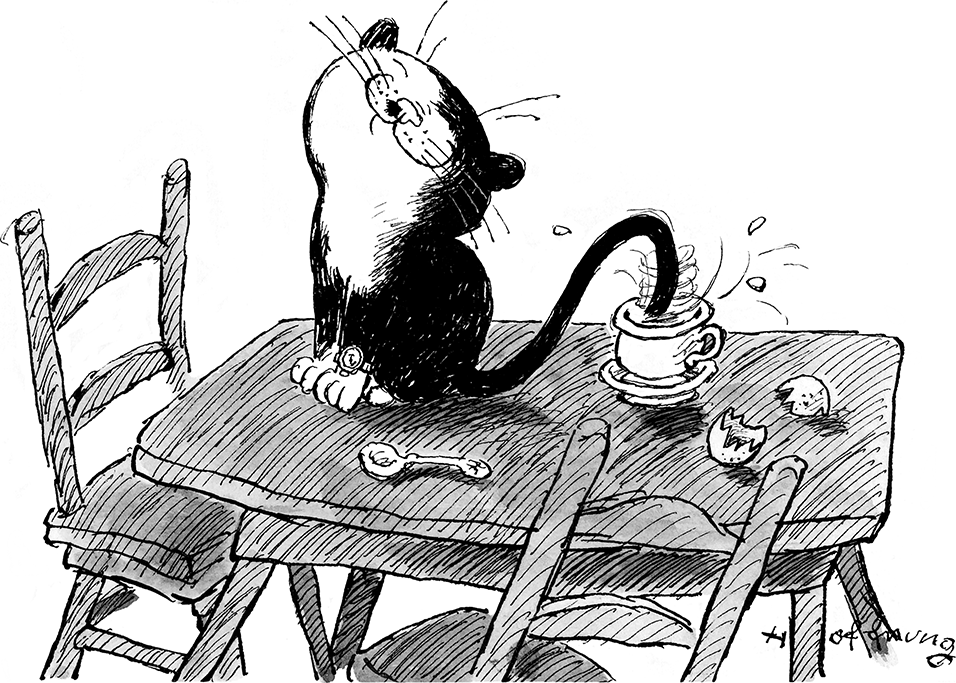

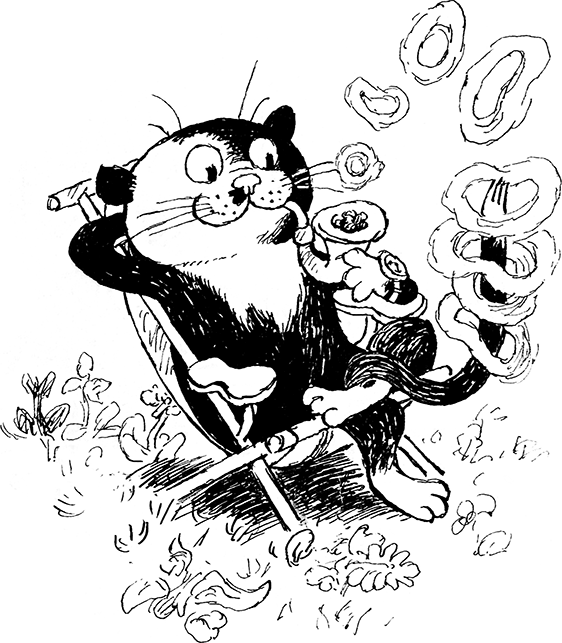

After Gerard and I married in 1952, I soon learned that I would have to share his love with Tim, his adored cat and the ‘heldentenor’ of the neighbourhood. Tim would absent himself from home, sometimes for days, returning (to the vast relief of Gerard) battered and scarred like some decrepit old warrior. Gerard was devoted to all cats in general and they abounded in Hampstead Garden Suburb. Any cat espied on a walk had to be properly greeted, caressed, conversed with and, in due course, taken leave of.

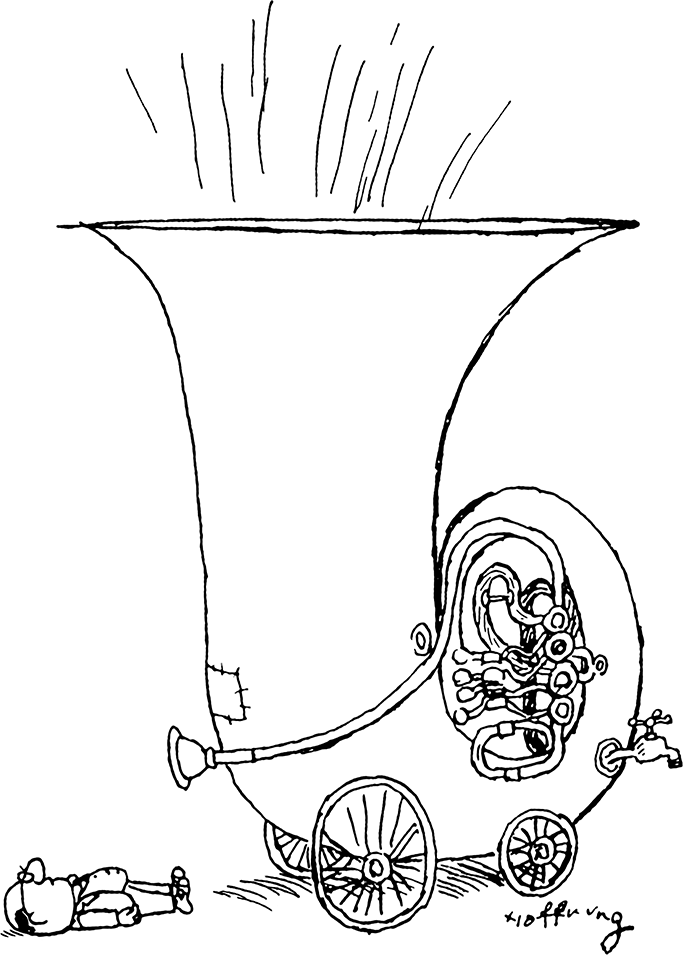

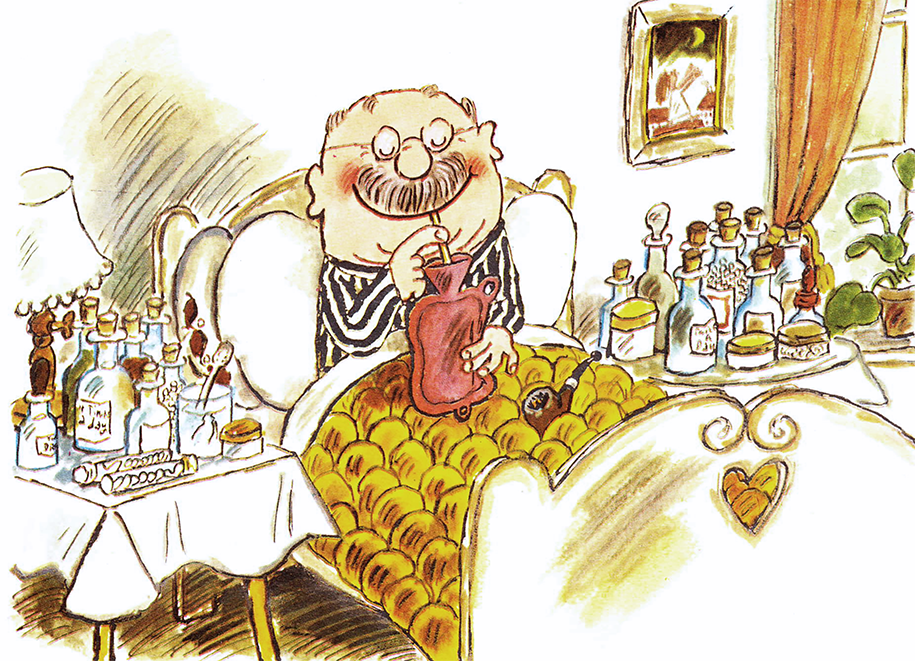

The other well-established member of the household at the time of my arrival was his tuba. There was no doubt about the seriousness with which Gerard took to practicing his tuba. Much of this took place on the landing, halfway up the stairs, where he found the acoustics most to his liking. He managed to wriggle his way into the Ernest Read Junior Orchestra and then, even more excitingly, into Morley College Symphony Orchestra, becoming its regular tuba player, vice president and court jester. The tuba, it seemed, had taken over our lives. Here we are actually living in one on our first Christmas together.

Gerard wrote articles about the tuba and would discuss it at the slightest provocation. When we went abroad there was a problem because it was too cumbersome to take. He would sneak out to the local music shops to see if, with any luck, he could arrange to try one out for a while. One of these visits resulted in a sale and our return journey was not one of the easiest.

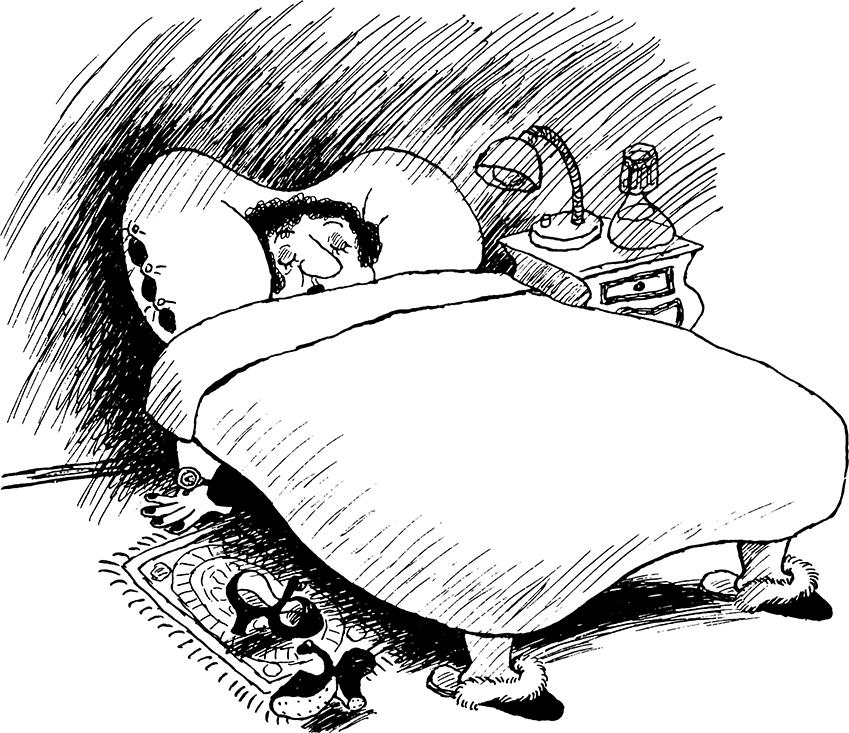

Writing to a friend, Gerard commented that it was so big that every time he played it he became exhausted and had to lie down for half an hour. Here is the illustration that he added to the letter.

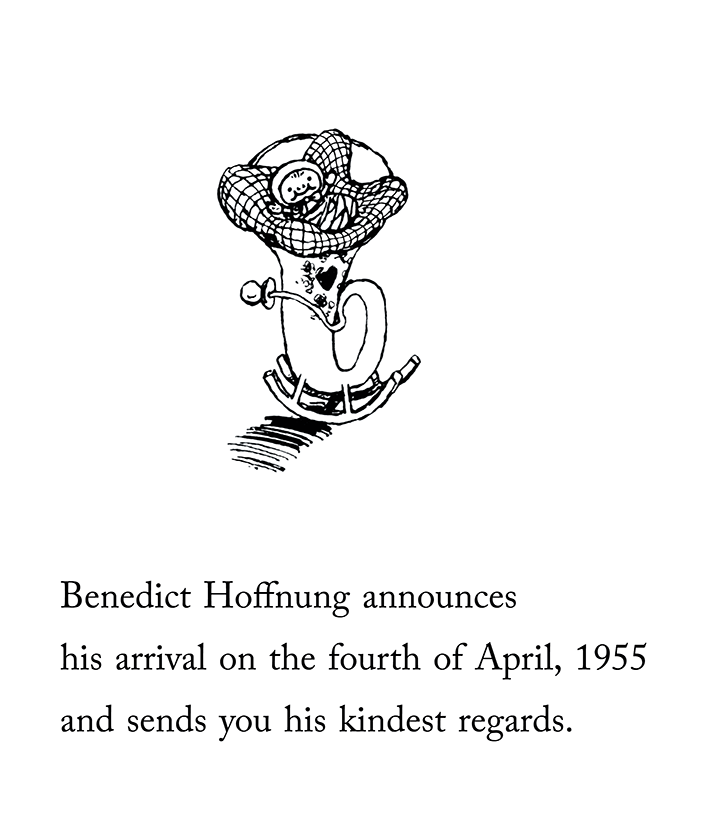

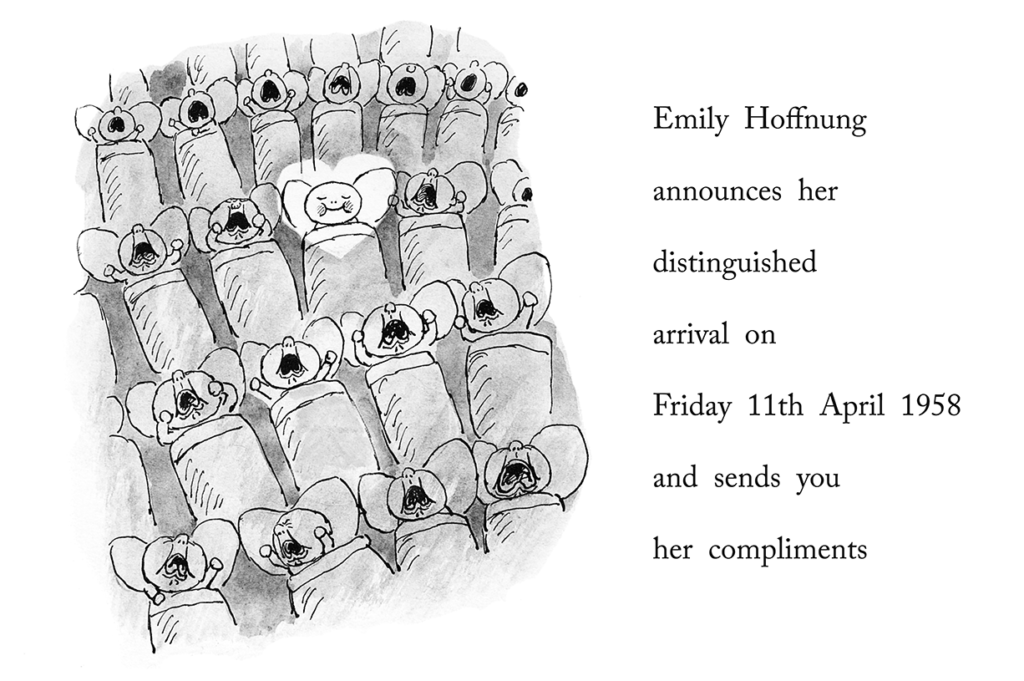

In our home, work and play combined and life was good. The arrival of our son Benedict in 1955 was one of the great joys of our life together, and the birth three years later of our daughter Emily completed our happiness.

Most aptly, Gerard at this time was illustrating a weekly article in the Daily Express written by Lady Elizabeth Pakenham and entitled Point for Parents. These articles, along with some of the illustrations, were published in a book of the same title. Later still, in 1961, a collection of the drawings only was brought out in a book called Hoffnung’s Little Ones.

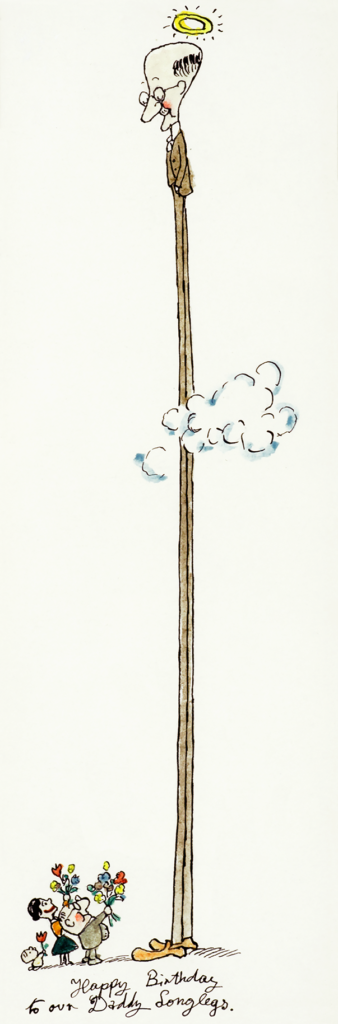

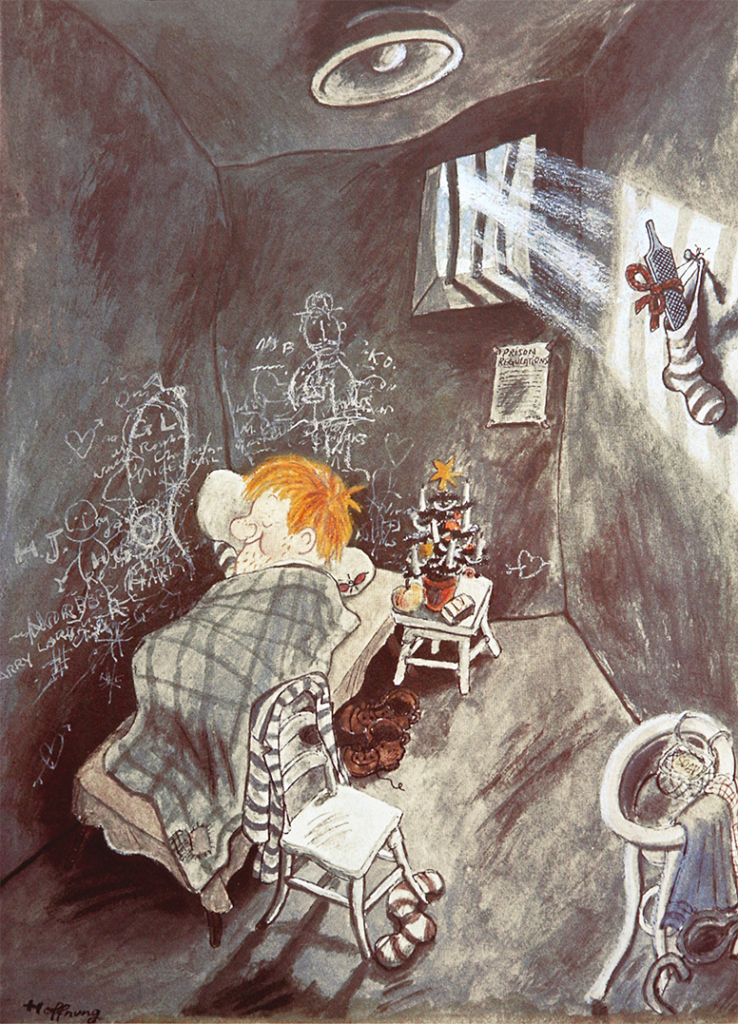

While on the subject of cards, here are some more Gerard designed: a birthday card sent to my father, whose height and slenderness were a constant fascination to Gerard; a Get Well card; the Royal Festival Hall’s Christmas card; a Christmas card featuring a prisoner.

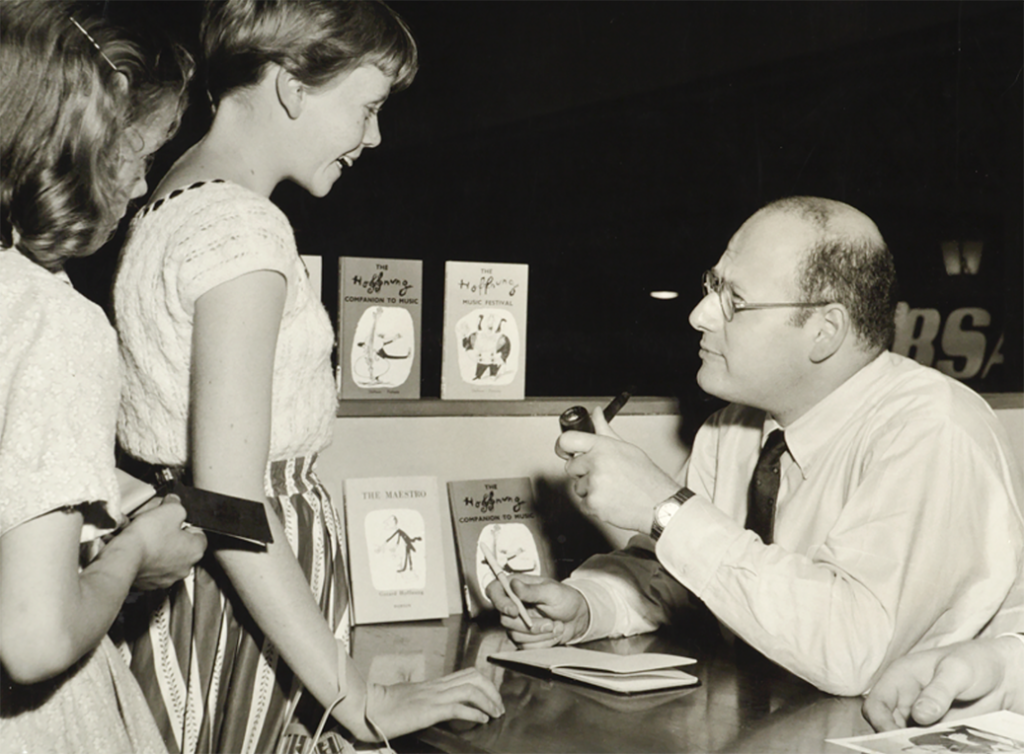

Having become an instrumentalist himself, Gerard had to observe his fellow performers with affection and tolerance. Unaware of its significance Gerard started to draw the little figure of a conductor exaggeratedly expressing a variety of orchestral moods. ‘…They might make a book…’ he mused. Several publishers thought not, but one did, and there began a collaboration with the firm Dobson Books. The little book, The Maestro, published in 1953, sold out rapidly and has been reprinted countless times. It was the first of a series of six musical-carton books which Gerard produced and was followed by The Hoffnung Symphony Orchestra, The Hoffnung Music Festival, The Hoffnung Companion to Music, Hoffnung’s Musical Chairs and Hoffnung’s Accoustics. They are irrepressible and remain as popular as ever throughout the world.

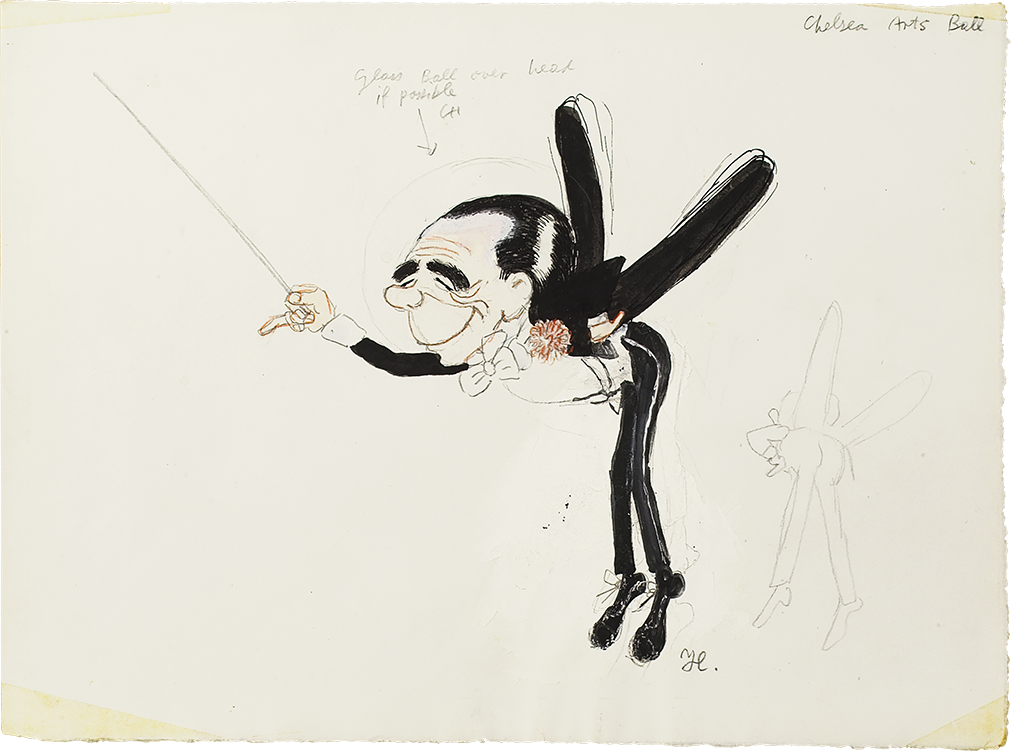

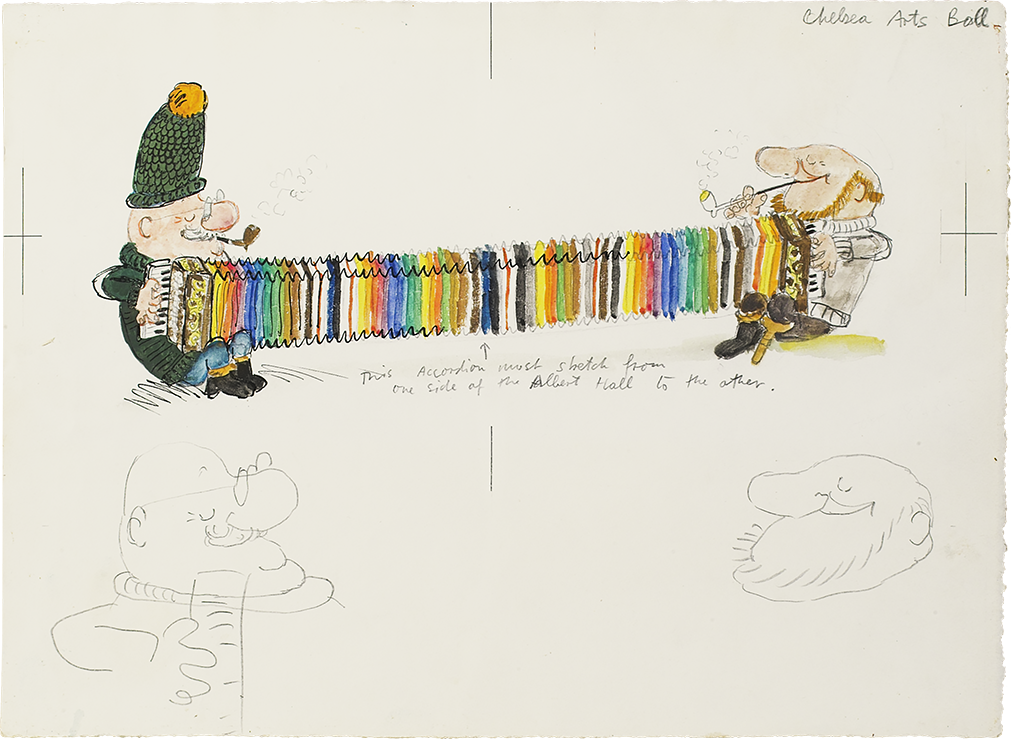

At this time Gerard was asked to design a number of models for the Chelsea Arts Ball, the traditional gala celebration held annually at the Royal Albert Hall by a host of art colleges. The designs in these drawings were made into models, most of which were hung from the dome of the hall.

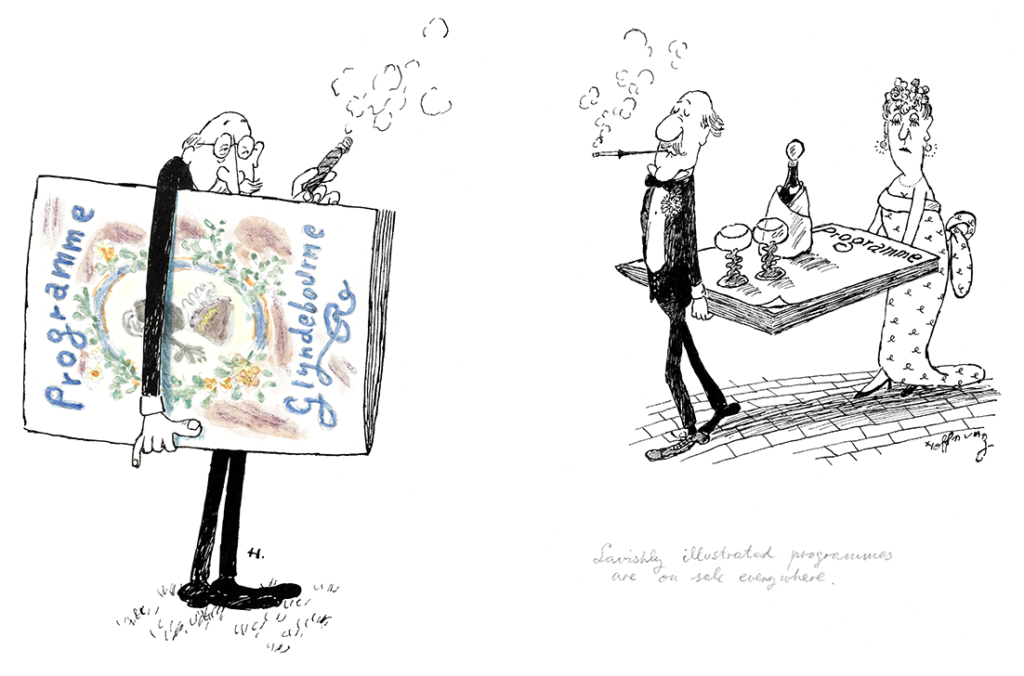

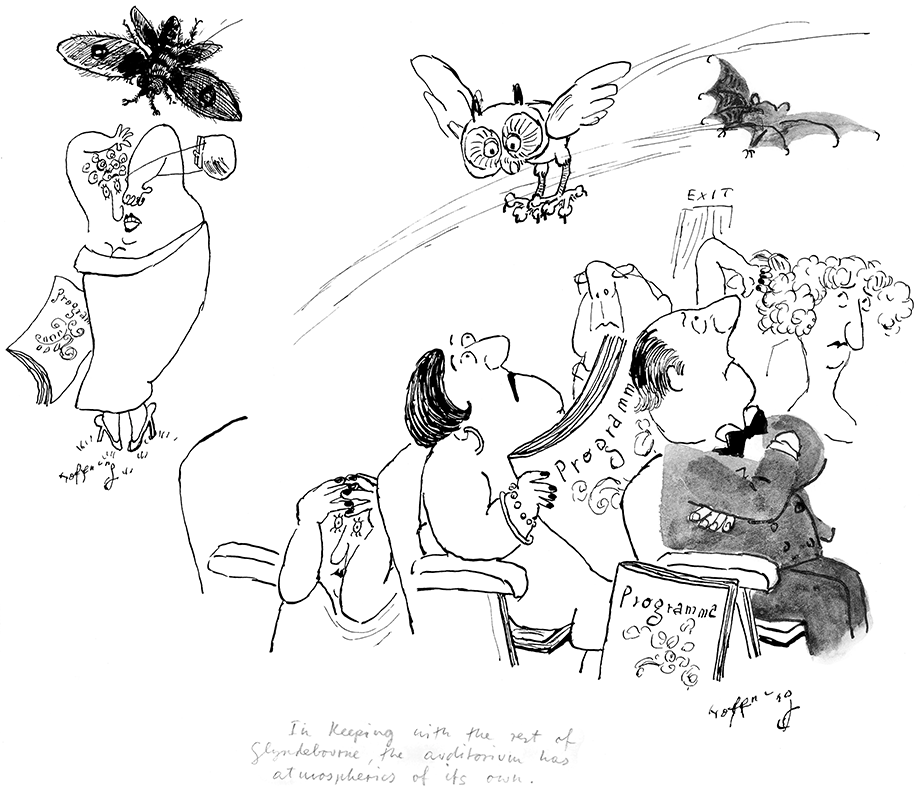

We spent a happy weekend at Glyndebourne, attending rehearsals and wandering through the grounds while Gerard explored ideas for a series of drawings for future Glyndebourne programmes.

Hoffnung Concerts

Please go to Concerts for detailed information about the Hoffnung Concerts.

FINAL YEARS, PRISON VISITOR

AND QUAKERISM

On several occasions Gerard announced that he felt he had not long to live. ‘I shall die young, you know,’ he would tell me quite seriously. How strange that I never took him up on this. What prompted this feeling? What was going on?

Of course one reason the conversation never progressed was that the prospect affected me so deeply I could not bear to contemplate it. Once when I protested at this appalling prediction he said comfortingly, ‘…Remember there will always be music and paintings and many good friends…’. I found this small comfort. Neither could I really believe that he was serious, that this larger-than-life, exuberant man with so much vitality and energy had any true presentiment of an early death. Sadly, his premonition was to be borne out by events.

One morning I was downstairs with the children seeing to last-minute preparations for lunch, when I heard him call. Sensing urgency in his voice I ran upstairs to his study and found him collapsed upon the sofa. I was in time to be with him for his brief remaining moments of consciousness. He died in hospital some two hours later from a cerebral haemorrhage. It was 28 September 1959 and he was 34 years old.

That he was a rare human being is certainly true. As a friend once remarked, God was kind to him and saw to it that his qualities and his gifts were endearing ones. They were there, too, from the very start, he displayed them constantly for all the world to see. They remained unchanged whatever the circumstances he encountered and difficulties he experienced. His secret, I am convinced, was his enormous humanity and warmth; after all, only these qualities can arouse reciprocal feelings of trust, enthusiasm and laughter. In our marriage, these qualities abounded, to the extent that I felt a sense of wonder at being part of this quite exceptional life. Perhaps his great humanity, so much reflected in his work, explains Gerard’s success in his lifetime and the high regard in which he is held today by so many people who never knew him.

As if to counterbalance his exuberance and effervescence, Gerard was also a very serious person, keenly aware of the major issues of the day including racial and homosexual prejudices, nuclear disarmament and prison reform which was a particular concern of his. These feelings are demonstrated here in another clip from the Oxford Union debate Life begins at 38:

After we married he became a prison visitor and in-between the demands that work made on his time he regularly went to visit prisoners at Pentonville prison. Merfyn Turner, social worker and prison visitor, founder of Norman House, a home for discharged prisoners in north London, wrote:

‘…Alf was one of Gerard’s men. He came to Norman House. He was unemployable, disorientated, schizophrenic; for twelve months we supported him until we were able to place him where he would be well cared for. But Alf disappeared, and was soon in prison again. For the next two years we kept in touch, mostly by letter. Alf’s letters were phonetic, often unintelligible. But one message was always clear: “Remember me to Hoffnung. Best friend I ever had…”’.

‘…In prison, rumour has the quality of reality, but the rumour that Gerard Hoffnung was dead was indeed reality. For the men who had the closest relationship with him, the shock was greater than they could absorb. “I don’t know what to think,” Stan said as he sat on his bed and looked at me as I sat where Gerard often sat before. “When my own mother died, I didn’t feel like this.”…’.

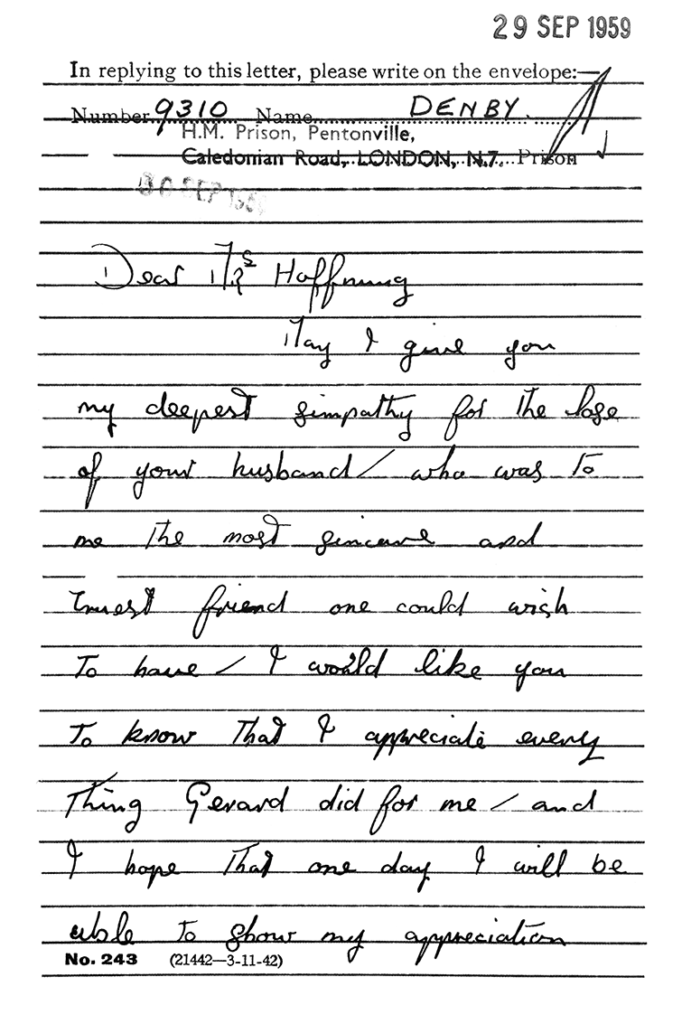

I received letters from Gerard’s men after his death; one reproduced here, expresses how much he meant to them:

For some time Gerard had been interested in the Religious Society of Friends – the Quakers. It was their deep-rooted concern for pacifism which first attracted him. He also sympathised with their concern for the individual, regardless of race, creed, nationality; their practical application of the Christian faith and their belief that all life is a sacrament. He found the uncluttered form of worship, its quietness and simplicity, appropriate for him and the remarkable potentiality of the silence helped further his quest for moral and spiritual meaning to our existence. With no priest or choir or ritual, a Quaker Meeting depends for the richness of its experience on its members and Gerard surely enriched the Meeting at Golders Green. Here is how Morag Morris, a close friend from meeting, remembered him:

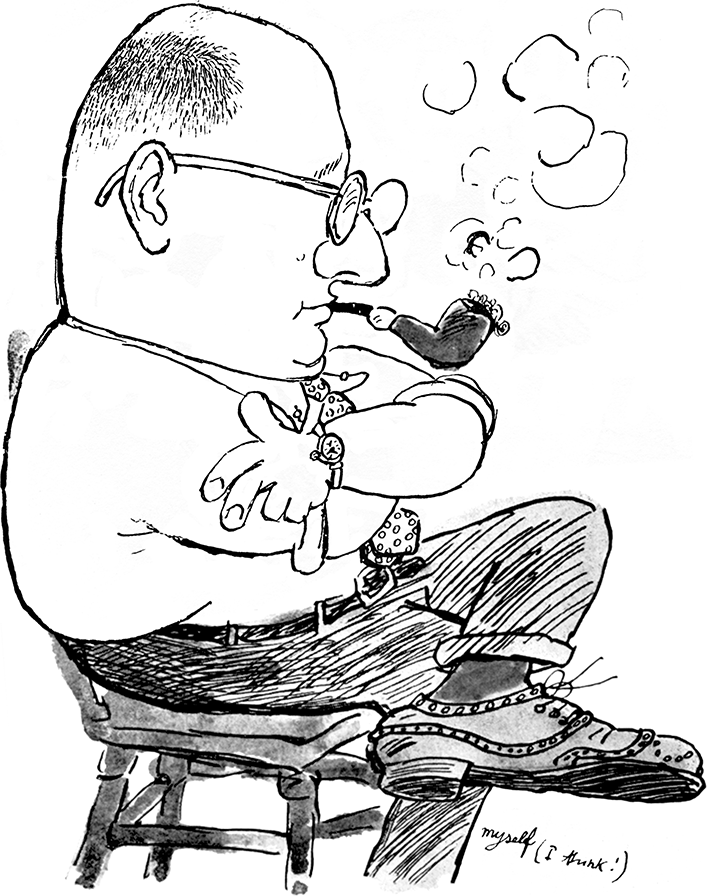

‘He was, usually, one of the later arrivals … He would tiptoe stealthily across the floor to the far side of the Meeting House, compact in a tweed suit or in an ample pullover of cherubic blue, or, once, in leather shorts braced and brief in German fashion. He would settle himself solemnly in one of the few armchairs, cross-legged, chin propped in cupped hand, frowning deeply. From time to time throughout the Meeting he would uncoil himself, to the minor discomfort of his neighbours (for which reason Annetta chose to sit far off) and knot himself up again, facing obliquely across the room. Or he would sit thoughtfully cracking his knuckles, one by one. In the main, though, he appeared sunk in contemplation, or attentive while some other member spoke.’

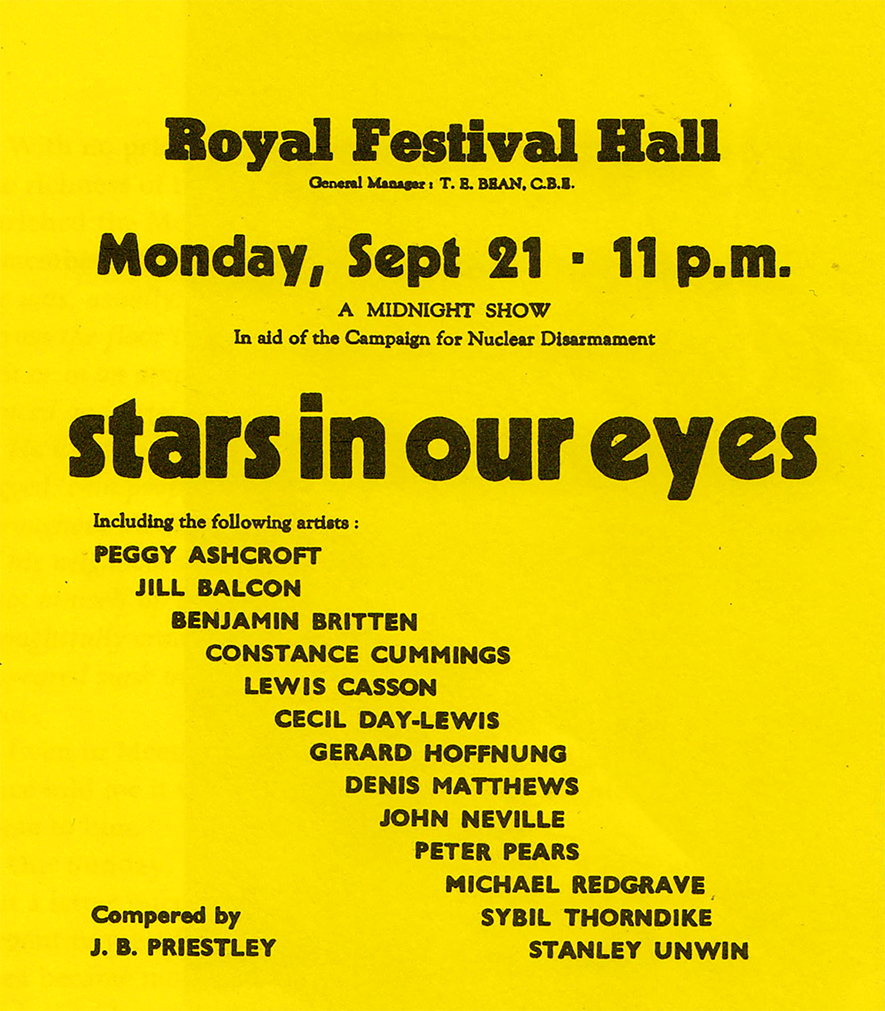

Looking into Gerard’s diary I see he opened the Hampstead Garden Suburb Horticultural Show on 19 September 1959 and on 21 September took part in a late-night concert ‘Stars in our Eyes’ at the Royal Festival Hall in aid of CND. Gerard was by now thoroughly at home with this concert platform, for apart from his own productions he had more recently been soloist there in a performance of Vaughan Williams’ Tuba Concerto with the Morley College Symphony Orchestra.

This time his tuba quartet performed a special arrangement by Wilfred Josephs (whose later compositions became delightful additions to the Hoffnung Concert repertoire) of the Pizzicato from Sylvia by Delibes. Altogether, with the distinguished cast, it was a great occasion. Surrounded by his friends, working for a cause he believed in and playing his beloved tuba, this was surely, a most fitting finale.

A week later on 28 September 1959, Gerard died. At his funeral service it was said that he was the first professional jester Quakers had known in 300 years. Gerard would have been pleased with this accolade.